The production of this online material was supported by the ATRIUM European Union project, under Grant Agreement n. 101132163 and is part of the DARIAH-Campus platform for learning resources for the digital humanities.

Rasterization

Rasterization is a primitive-order image synthesis architecture that processes a stream of primitives and converts them into a raster, i.e. an array of dense pixel samples, at the sampling rate of an image buffer. Each pixel sample is shaded individually and independently from all other pixels. The shaded pixel samples are then appropriately blended and combined with the already generated and stored samples in the image buffer to form the final image. A primary concern for image correctness in rasterization is the the elimination of hidden surfaces. The method is a primitive-order one in the sense that rendering is executed on primitives and each primitive is rasterized once per rendering pass, while the same image pixel location may be independently accessed for updates by multiple primitives overlapping in image space. Rasterization is fully implemented in hardware in all modern GPUs and is the mainstay for interactive rendering, due to its simplicity, efficiency, scalability and high performance.

The primary rasterization primitive is the triangle. Being convex by default, it greatly simplifies sample containment testing and therefore the rasterization process. Other important rasterization primitives are line segments and points. This small set of elementary primitives is adequate to sufficiently approximate other surfaces, since any polygonal surface can be constructed using triangles and linear segments can approximate any boundary curve.

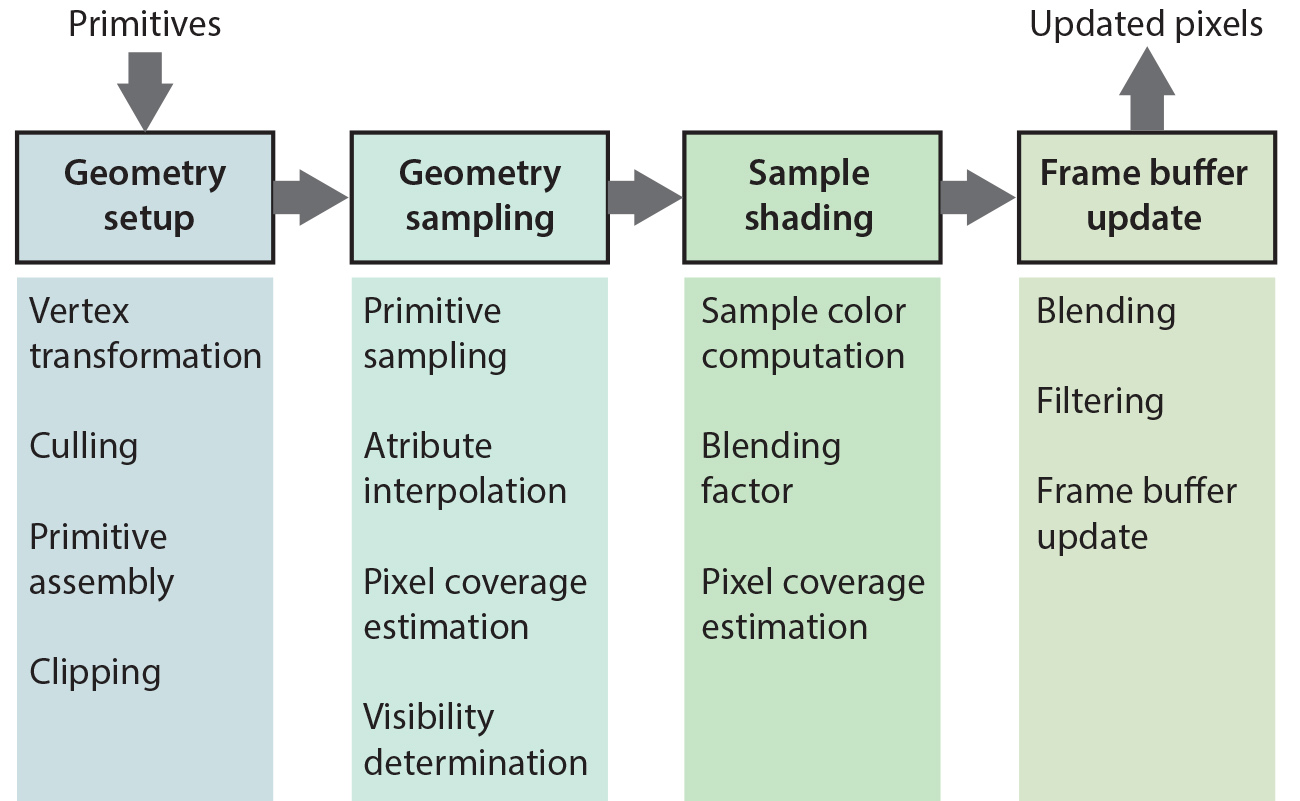

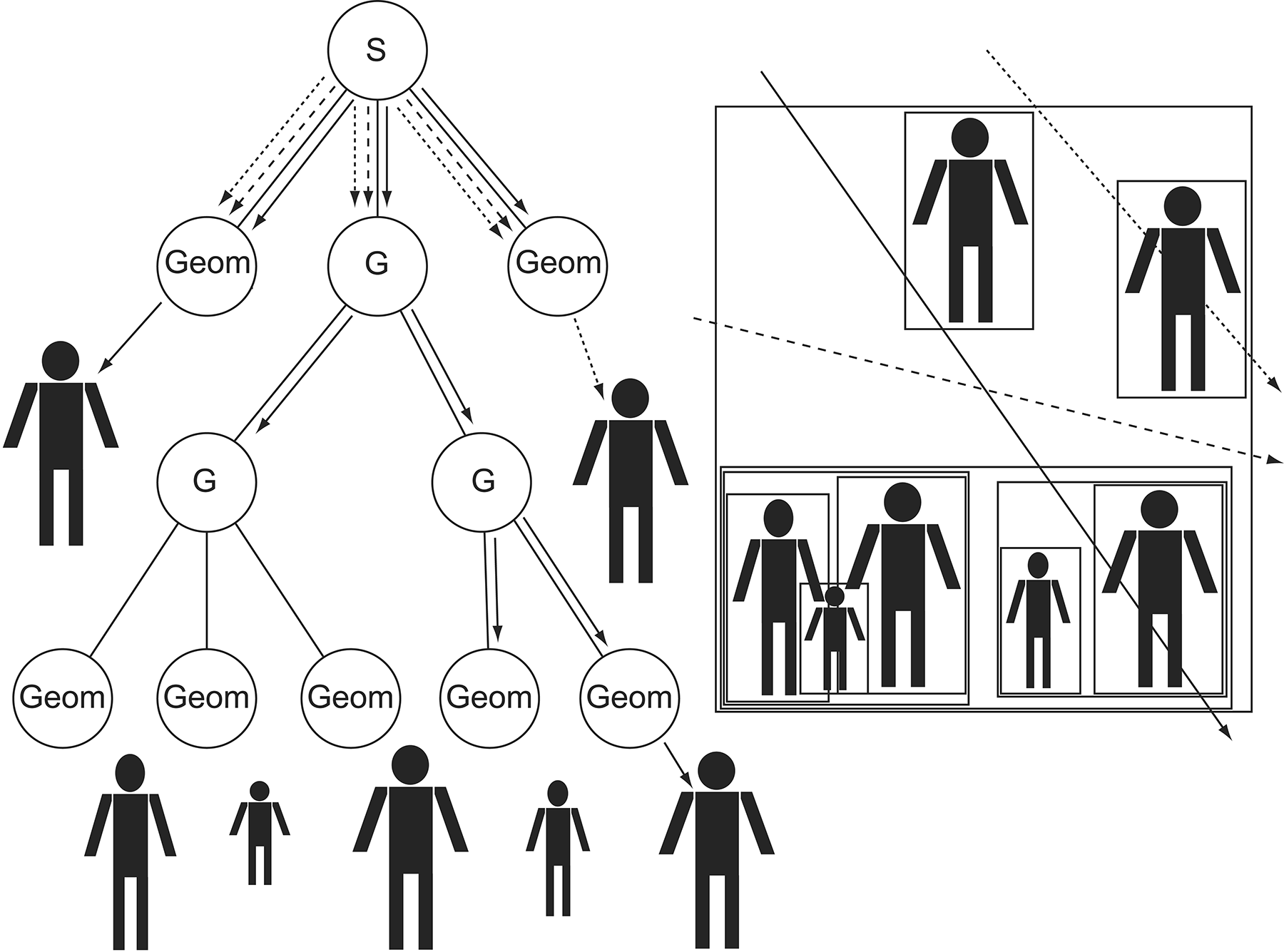

The Rasterization Pipeline

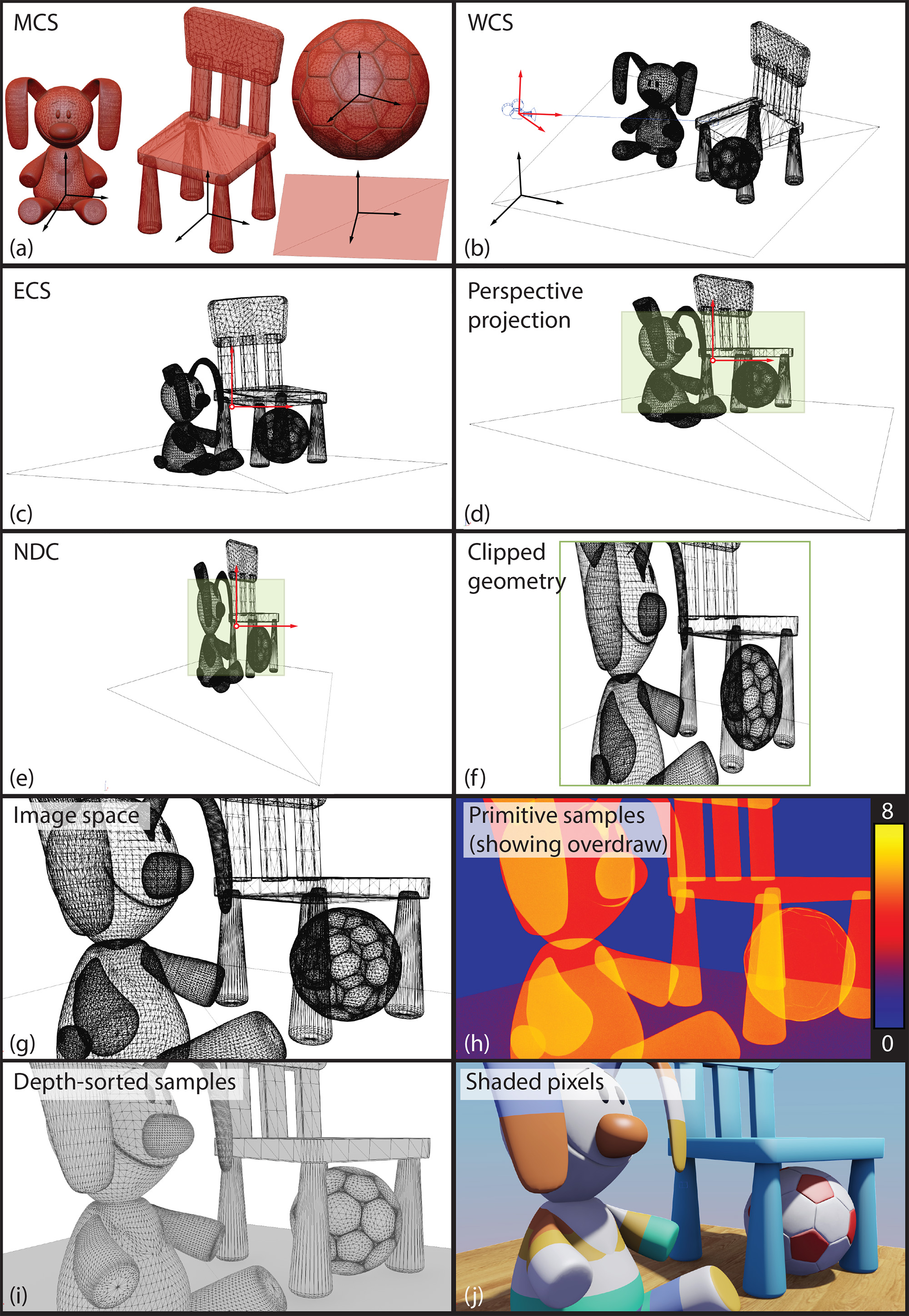

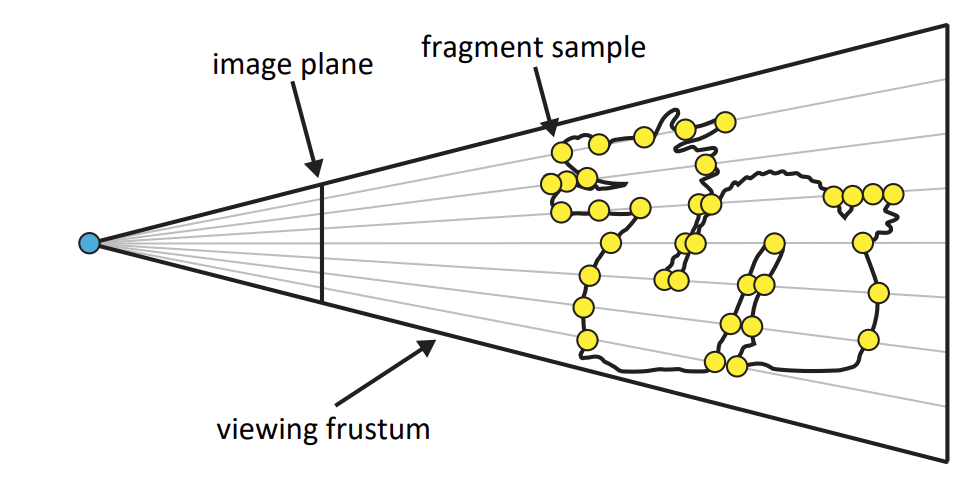

An overview of the rasterization pipeline is shown in the following figure. Primitive vertices are first transformed from the local (model) coordinate system of the object they belong to and then projected, obtaining their normalized device coordinates. Then the corresponding primitives are assembled and processed. Processing includes potential clipping and triangulation, tesselation, further vertex re-arrangement, primitive conversion or selective elimination.

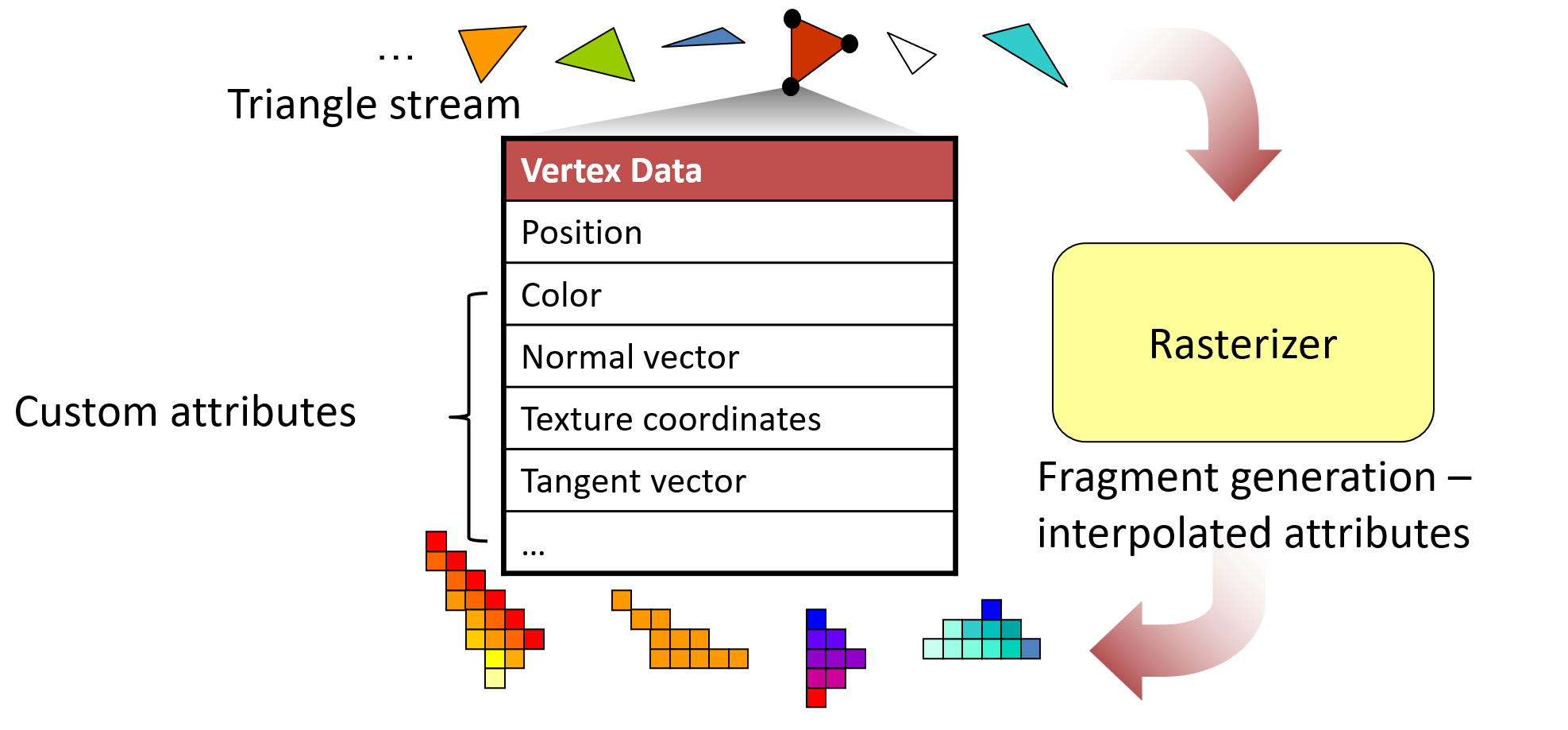

Next comes the dicing of a primitive into pixel-sized samples. These need to be efficiently determined (see below) and densely drawn, forming a contiguous region of pixels laid out on a grid within the boundaries of the rasterized primitive. For each generated primitive sample, the vertex attributes of the primitive are interpolated to obtain the corresponding values at the sample location. These are later used in the pixel shading operations for computing the color of the pixel sample. The pixel sample along with the record of interpolated attributes associated with it are often called a fragment1 to indicate that this is the smallest, indivisible piece of information that moves through the pipeline and to signify a potential decoupling between this token and the pixel, as sometimes the rasterization rate may differ from the final image buffer resolution.

A mandatory interpolated attribute that has a special significance for the rasterization pipeline is the sample’s normalized depth, i.e. its normalized distance from the center of projection. This value is used for the hidden surface elimination task, i.e. the determination of the visible samples and the discarding of any samples lying beyond the already computed parts of the geometry that cover a specific pixel. This test is typically performed as early as possible, i.e. after the sample’s depth has been determined, in order to reject non-visible samples as soon as possible. Depending on the specifics of the shading stage however, which may alter the state of the pixel sample, this test may be deferred to follow shading.

Since a primitive may not fully cover a pixel, being either too small or just partially intersecting the pixel, the pixel coverage may be optionally estimated, so that the assignment of the respective computed color to the frame buffer can be blended according to it, smoothly transitioning from the interior of the primitive to the "background" (see also antialiasing below).

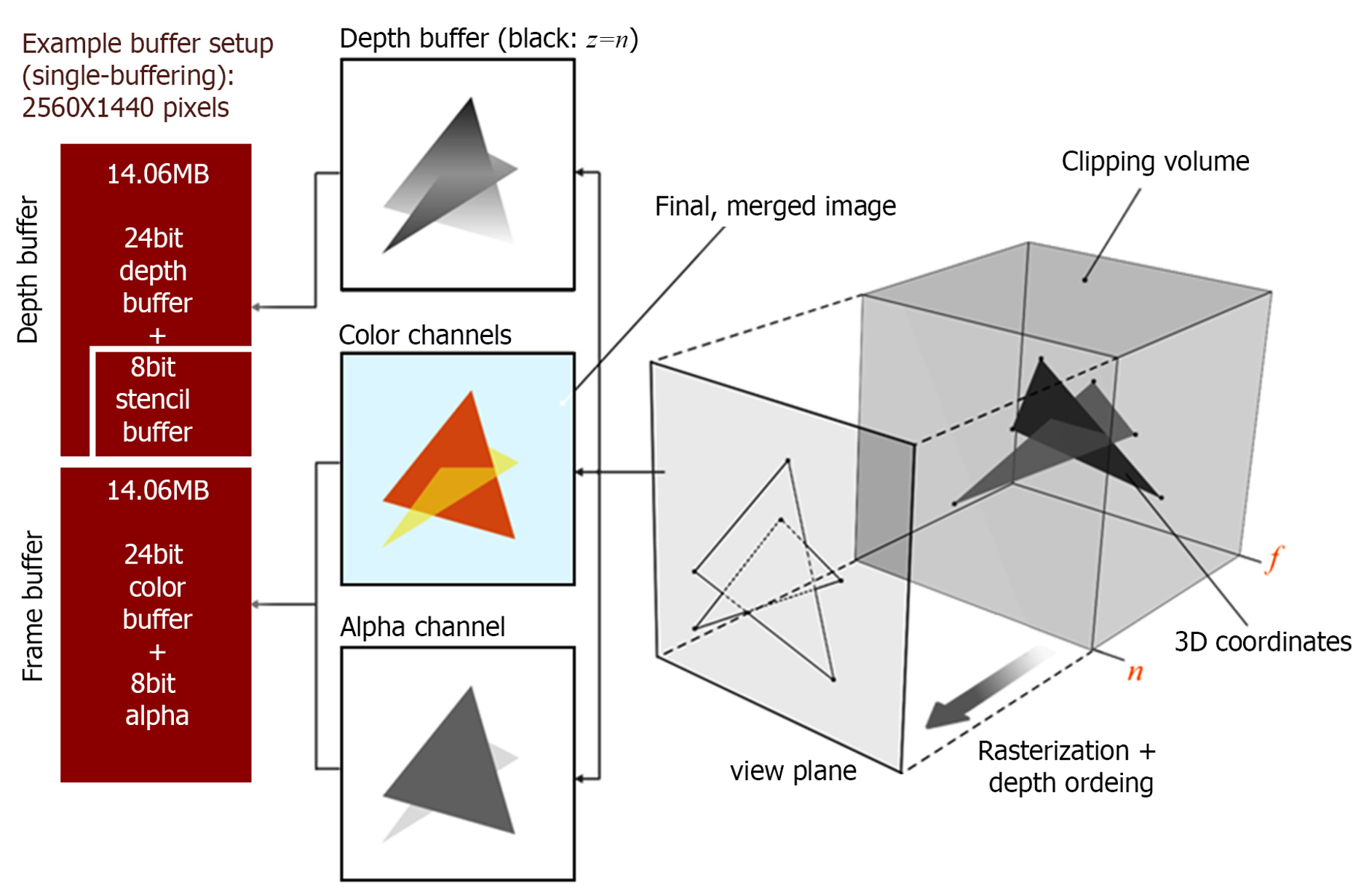

After the sample generation, each record of per-pixel interpolated attributes is forwarded for shading, in a specific programmable stage, whose task is to compute the color of the current sample to be written to the designated output frame buffer. The allocation and specification of the output buffer in terms of format and dimensions is part of the pipeline setup. Please note that the frame buffer may correspond to the device’s output buffer to be accessed by the display terminal or an intermediate memory buffer allocated for the pipeline in GPU-addressable memory. Unless a plain color is output for a pixel sample, the fragment or pixel shading stage usually performs the most intensive computations, since it computes texturing and lighting to determine the output color. Additionally, this stage also calculates and assigns a "presence" value for the computed sample color, called the alpha value. This is typically used as a blending factor to mix the currently estimated pixel color with the color already present in the frame buffer, from the display of other primitives in the same pass. This is why the alpha value is involved in rasterizing surfaces with transparency 2.

The last stage of the simple forward rasterization pipeline is the deposition of the computed color for a given pixel onto the frame buffer either by substitution or blending of the underlying values. Blending adheres to specific rules that are governed by the blending function chosen and enabled, such as linear or additive blending. The alpha value of the new (source) fragment and optionally that of the existing (target) value are used as blending factors in this process. The GPU architecture handles the frame buffer update synchronization, to avoid conflicts when multiple triangles attempt to write at the same pixel location. Other clashes are avoided by explicitly generating a single sample per pixel per primitive.

The following figure presents a sequence of operations applied to the vertices of primitives, the primitives and the generated samples to form the final image.

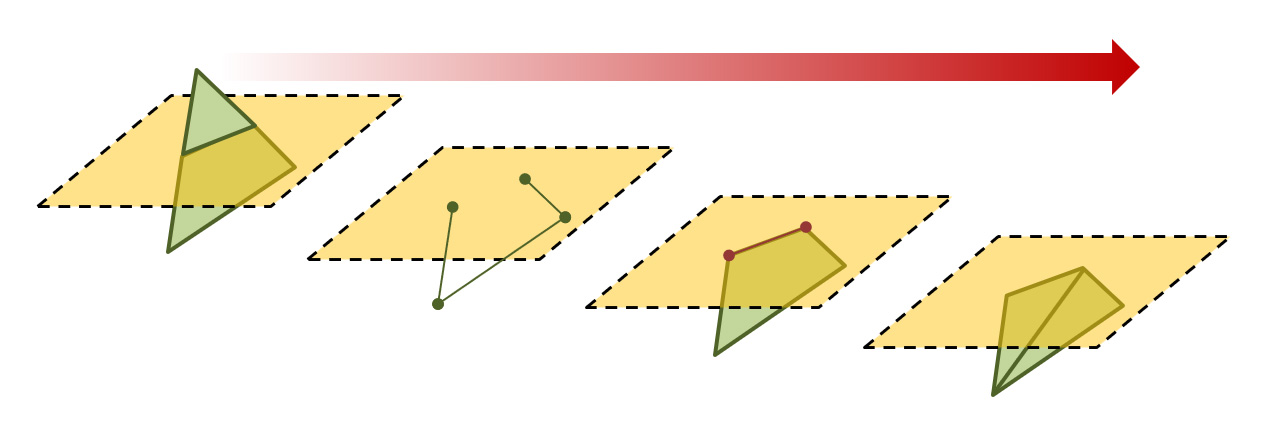

Clipping

Clipping is a general computer graphics task that involves cutting out parts of one primitive against the outline of another and usually involves polygonal boundaries or linear segments. It is an important process for geometry processing and rendering as it allows computing intersections between primitives. In the case of the rasterization pipeline, we are interested in discarding parts of primitives that cross the boundaries of the view frustum and in particular the near clipping plane (see projections), since attributes interpolated for coordinates closer that the near clipping distance will be warped and in general, ill-defined. In principle, any clipping step we may perform on the near clipping plane we can repeat for the rest of the boundary planes of the frustum. However, it is more efficient to delay this until rasterization and perform the clipping in image space.

Clipping triangles in general results in convex polygons with more vertices. In the case of single-plane clipping (near plane), at most 6 vertices may be produced after clipping the triangular boundary by a quadrilateral viewport. Therefore, clipped triangles often need re-triangulation, which is trivial to implement for convex polygons, by constructing a fan-like collection of triangles to connect the vertices of the resulting boundary.

Sampling and Interpolation

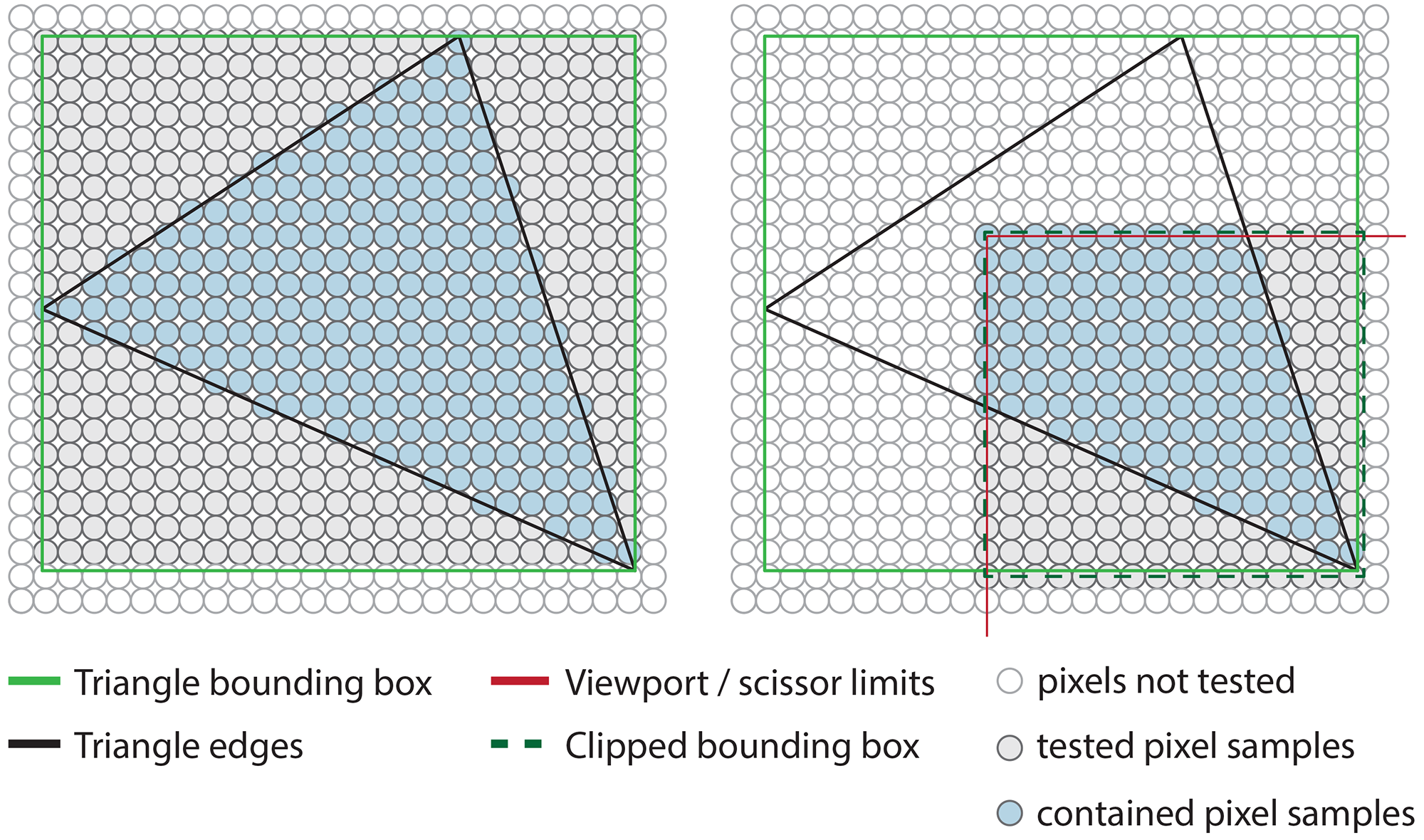

To compute the raster of a triangle, one needs to determine which pixels od the rendered image region are contained within the boundary of the triangle. First, the subset of potentially included pixels is determined, to avoid testing trivially external positions. One an do this by limiting the search for contained pixels to the intersection of the actual active rendering region and the horizontal and vertical extents of the triangle (see next figure - right). For each eligible candidate pixel, we test its relative position with respect to the three edges of the triangle, by means of an edge equation value, i.e. a specially constructed mathematical equation based on the coordinates of two consecutive triangle vertices, whose sign, when applied to the pixel’s coordinates, can determine which side of the boundary the pixel rests on. If the sign of this equation for a particular pixel is the same for all edges of the triangle, then the pixel is definitely inside the triangle and needs to be drawn. The calculation of the edge equations is very efficient, with most terms being computed once per triangle. Furthermore, the containment test can be trivially performed in parallel for all candidate pixels.

The geometric and textural properties for all interior pixels of triangle must be determined prior to forwarding these pixel samples for shading. Many user-defined properties may be uniform across the area of a triangle, e.g. a flat color, but typically, we need the attributes that we have assigned to the three vertices of the triangle interpolated inside its covered portion of the raster, to smoothly vary them across the triangle’s surface. There are also certain geometric aspects of the triangle that must be interpolated and especially the depth of the pixel sample, i.e. the third pixel coordinate (the other two being its image and coordinates).

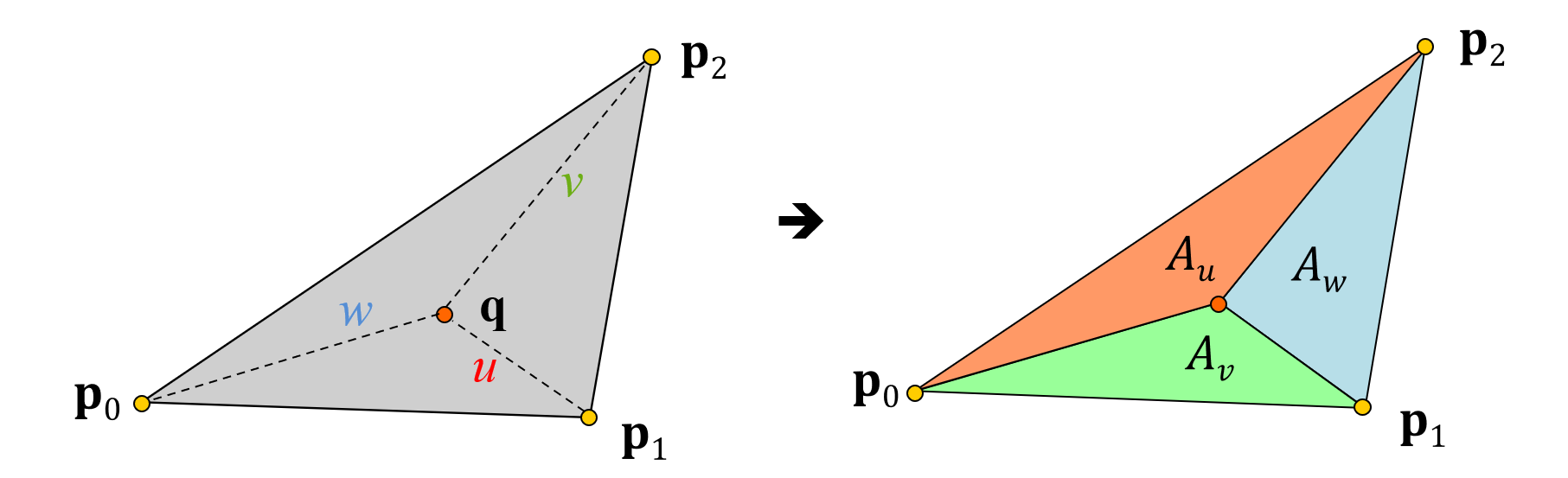

For each pixel that passes the containment test during rasterization, its attributes are interpolated and a fragment record is filled with the corresponding values. These will be later used for the shading of that pixel. The interpolation of the attributes itself is based on the three barycentric coordinates of the pixel’s position relative to the three vertices of the triangle (see figure below). The closer the pixel lies to a vertex, the larger is this vertex’s contribution to the linear blend of attributes that defines the interpolated values for the pixel. The barycentric coordinates are directly computed from the edge equation values for the point in question, with minimal extra overhead. The combined computation is very efficiently implemented in hardware and this is why the rasterization stage is quite fast.

It is important to make a note here about a particular trait of rasterization that prevents it from being very efficient when rendering very small primitives. Pixel interpolation computations are done in pixel clusters and not for individual pixels. This is due to the fact that for shading computations that involve the determination of a mipmap level for one or more textures or certain calculations that involve image-domain attribute derivatives, the differences of the interpolated attributes with respect to neighboring pixels must be computed, even if these neighboring pixels are not part of the triangle interior. This is the case for boundary pixels and pixel-sized triangles. Therefore, it is more efficient to draw fewer large triangles, rather than many small ones. For the same reason, certain rasterization-based rendering engines have opted to handle the rendering of very small primitives with custom software implementations of rasterization rather than relying on the generic hardware rasterization units of a GPU3.

Hidden Surface Elimination

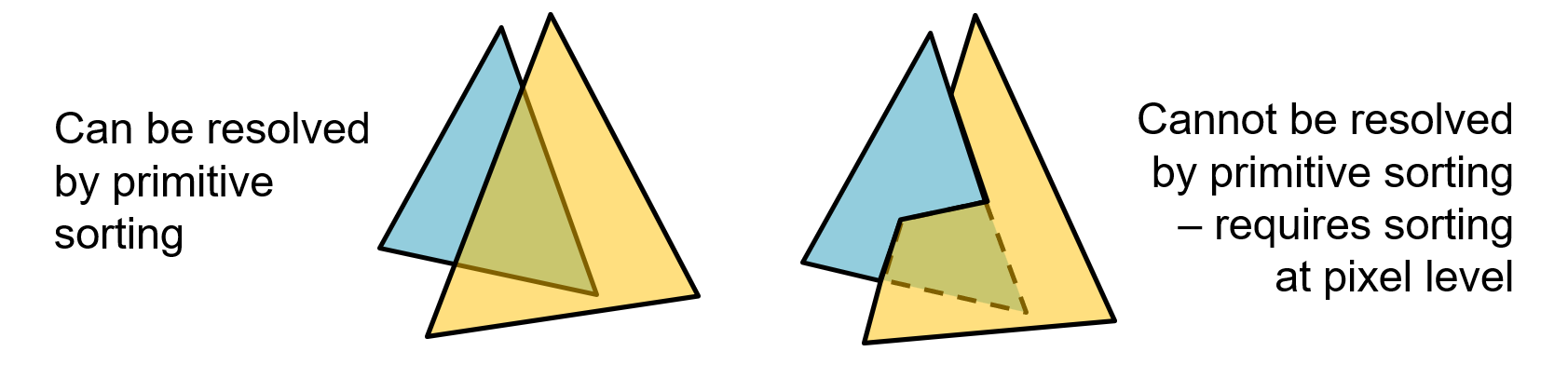

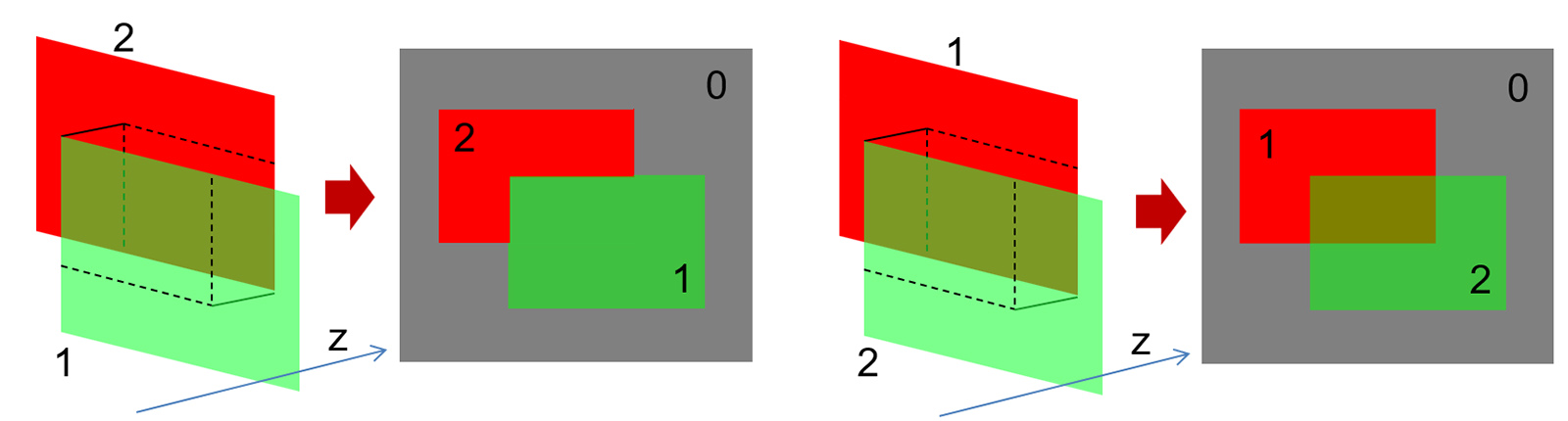

As explained in the introduction, in computer graphics, the task of hidden surface elimination is crucial for delivering a correct depiction of the order of presented surfaces and layers. Remember that in rasterization, all vertex coordinates have been first transformed to eye coordinates and then projected on the image plane. However, we cannot simply sort the triangles according to a layer or z-offset ordering, because this is an ill-defined problem; depth intervals of triangle edges may be overlapping and worse, triangles may just as well be intersecting each other, as shown in the next figure. Therefore, determining the closest, "visible" surface of a collection of triangles must be done at the smallest, atomic level of representation, i.e. the pixel. This is why, during the projection of a vertex on the image plane, its coordinate is not simply dropped, but is rather maintained either in its initial, linear form or in some other monotonic transformation, to be used for per-pixel depth comparisons in hidden surface elimination tests.

The easiest and most popular way to perform hidden surface elimination in the rasterization pipeline is the z-buffer algorithm. To implement the method, a special buffer, the depth buffer, equal in dimensions to the generated image is allocated and maintained, where the closest pixel depth values encountered so far during the generation of a single frame are stored. The depth values are typically normalized. At the beginning of each frame’s rendering pass, the depth buffer is cleared to the farthest possible value. For each interior triangle pixel sample generated by the rasterizer, its depth is compared to the existing value stored in the corresponding location in the depth buffer. IF the new sample’s depth is closer to the origin, the old depth value is replaced and the pixel sample is said to have "passed" the depth test; the sample’s fragment record is forwarded for shading. Otherwise, in the case of a failed depth test, the new sample is considered "hidden" and is discarded, undergoing no further processing.

Extending the mechanism of depth testing a little, the depth test itself can be changed from retaining the closest values to alternative comparisons, such as keeping the farthest or equidistant pixel samples, in order to manipulate the visual results and perform special rendering passes to implement specific algorithms and special effects. Furthermore, the depth buffer can be cleared to arbitrary values and the depth test can be completely switched off. This behavior is fully controlled by the application, which can set the appropriate rasterization pipeline state for the task at hand.

The depth test is triggered most of the time before shading, right after fragment interpolation, as it is prudent to avoid the expensive shading computations if the pixel sample is going to be eventually discarded as hidden behind other parts. However, there are certain rare shading operations that can unexpectedly alter the interpolated depth of a fragment and therefore, the depth cannot be relied upon for hidden surface elimination prior to shading. For these cases, the depth testing is performed after shading, introducing substantial overhead to the pipeline, since shading is performed for all generated pixel samples instead of only the visible ones.

Pixel Shading

The pixel coordinates inside a triangle marked for display are queued for shading. Since the rasterization pipeline enforces pixel independence, each primitive pixel sample is treated in isolation, meaning that it cannot access image-space information from neighboring image locations from the current image synthesis pass. However, we will discuss later on techniques that rely on multiple rendering passes, which enable the (re-)use of image-domain data at arbitrary pixels generated in previous stages to implement more complex shading algorithms.

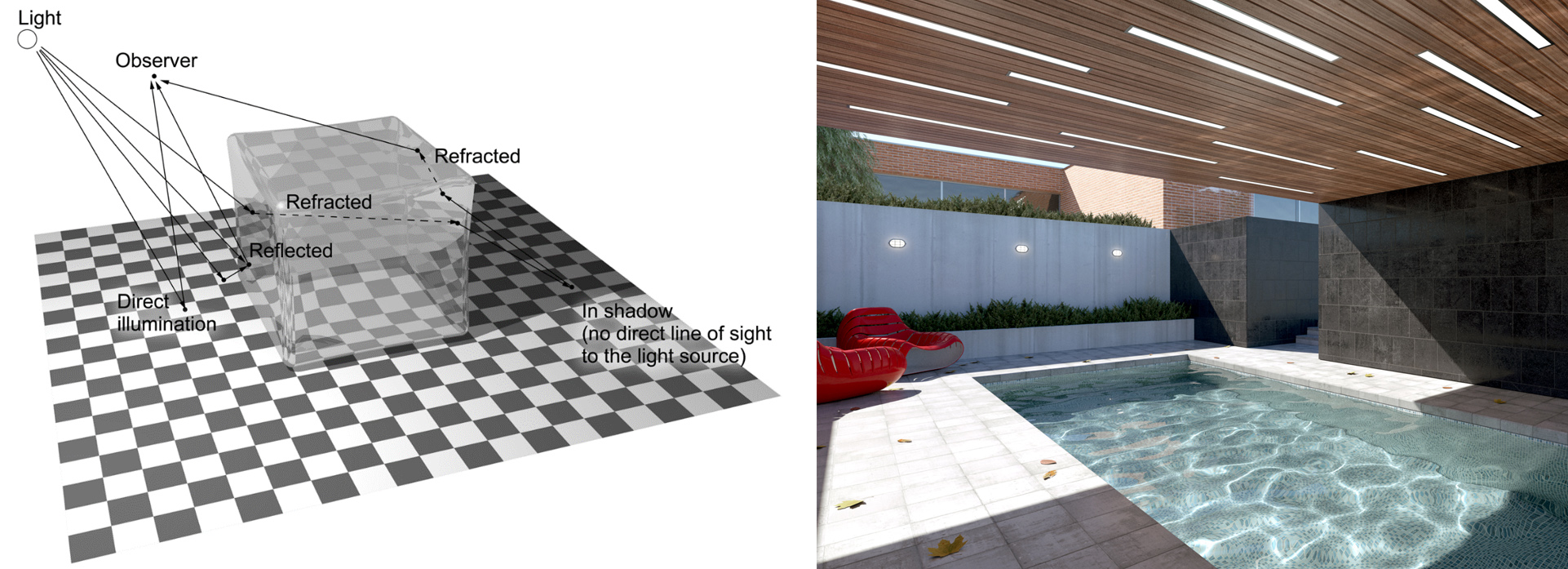

In rasterization, shading involves the determination of a pixel sample’s color prior to updating the frame buffer and the determination of a presence factor, the alpha value, which is used for compositing the resulting color with the existing values in the same pixel location of the frame buffer. Shading alone is a common operation in all rendering pipelines, as shown in the appearance unit. However, the geometric and material attributes involved are computed differently in each pipeline and certain phenomena and light-matter interactions may not be possible to compute. Rasterization, relying on local geometric information alone, is incapable of estimating lighting contributions coming from other surfaces and therefore, in its basic form, it cannot compute indirect lighting, including reflections and proper refraction.

A typical single primitive rasterization pass that directly computes the shaded surface of primitives in the frame buffer, is called a forward rendering pass. The typical computations involved are the sampling of textures referenced by the geometry to obtain the local material attributes, the estimation of direct lighting from provided light sources, potentially involving light visibility (shadows). The alpha value of the shaded sample is also computed, but the particular stage does not control how it is going to be exploited by the rasterization pipeline. Furthermore, the shading algorithm my opt to completely discard the current fragment. This is particularly useful when attempting to render perforated geometry, where a texture layer provides an (alpha) mask for this purpose or the value is computed procedurally.

Optimizations

Since rasterization is a primitive-order projection-based approach to rendering, primitives not directly in view, play no part in the formation of the final image, at least for opaque objects. This means that if the visibility of entire clusters of primitives can be quickly determined prior to rasterization, these can be discarded early on, significantly reducing the processing load.

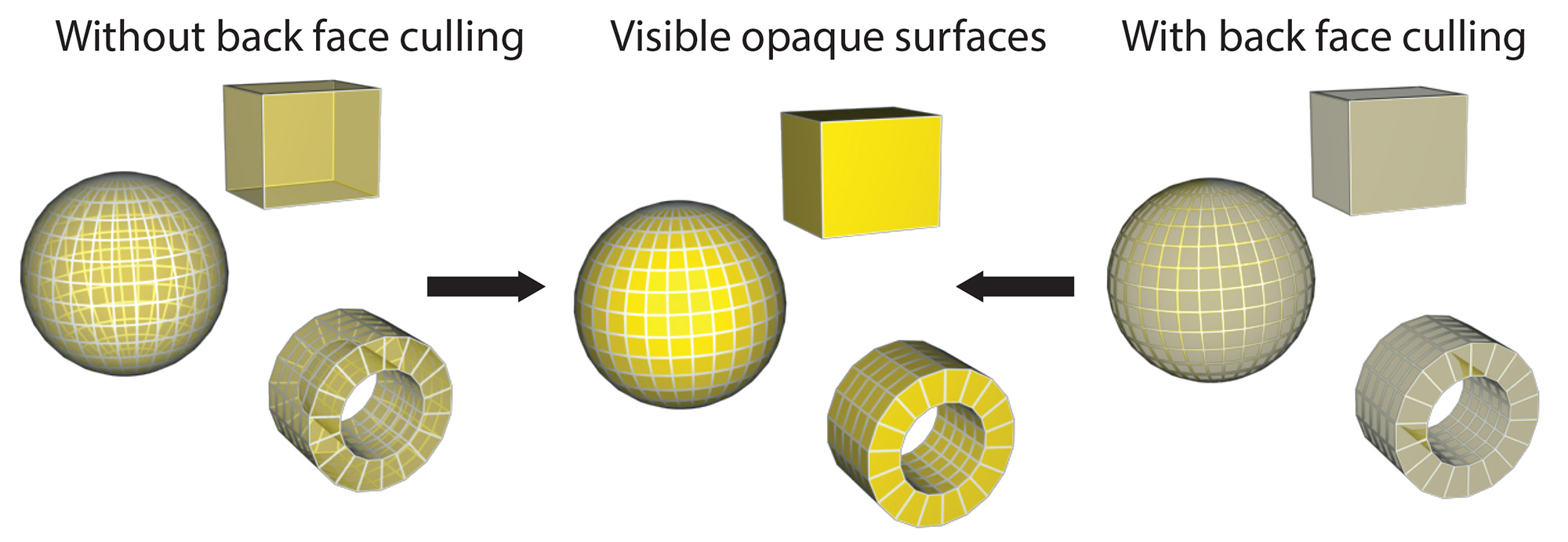

Back-face Culling

One of the easiest to test yet effective conditions for discarding geometry is back-face culling. It boils down to eliminating all polygons that are facing towards the front camera direction, i.e. they are showing their "back", or internal side to the view plane. The rationale behind this criterion is that at least for watertight objects, i.e. objects that are formed from closed surfaces with no gaps in the polygonal mesh, front-facing polygons should always be closer to the center of projection and therefore they should cover the back-facing ones anyway. Culling of the back-facing polygons is easily done by checking the sign of the coordinate of the geometric normal vector of the triangle’s plane, after projection, i.e. in clip space. The method is very efficient, eliminating on average 50% of the polygons to be displayed, regardless of viewing configuration. It is also orthogonal to other early culling techniques.

Keep in mind that the method is not generally applicable to transparent geometry, since the elimination of the back faces will be noticeable through the display of transparent front-facing polygons.

Hierarchical Depth Buffer

A hierarchical depth (Z) buffer (HiZ for short) organizes the depth buffer pixels in uniform blocks. Each block maintains the minimum and/or maximum depth values of the contained pixels and is updated each time a new fragment passes the depth test. This scheme can be recursively organized in more than two levels, by aggregating blocks in larger super-blocks. The hierarchical depth buffer can be used to accelerate various tasks, the most important being early fragment rejection: Since primitive fragments are (bi-)linearly interpolated, we can safely assume that, if the 4 corners of a block of fragments are contained within the boundaries of a primitive, we can check the minimum and maximum Z value and if outside the respective maximum and minimum values recorded as the block’s extents, the entire patch of fragments is rejected or accepted, without testing individual fragments. Another important use of the HiZ mechanism is the hierarchical screen-space ray marching that can be exploited for quickly skipping empty space when tracing rays in the image domain. Please read more on this, latter in this unit. higher levels of the HiZ construct are also utilized in occlusion culling, as they provide a "safer margin", a cheaper, low-resolution image space and a more cache-coherent way to query objects for visibility behind other, already drawn elements of a scene (see below).

Frustum culling

Since there is no indirect contribution of illumination coming from off-screen polygons to the generated image in rasterization, all geometry outside the view frustum can be eliminated right from the start. However, testing each and every polygon against the sides of the polyhedral clipping volume of the camera extents is not efficient, especially for large polygonal environments, negating the benefits of such an attempt. On the other hand, if we consider culling at the object level instead of the polygon one, far fewer tests are being executed per frame. For example, consider a forest consisting of 500 trees. Let us also assume an average polygon count of 10,000 triangles per tree. Attempting to draw the entire population of trees would result in emitting 5,000,000 triangles for rendering, which is very wasteful if the camera captures an angle from within or close to the forested area. attempting to cull this number of triangles is impractical, too. However, if we consider a simple bounding volume for each tree, such as its axes-aligned bounding box (AABB - see Geometry unit), then we only need to test 500 such simple primitives against the camera frustum, quickly eliminating thousands of triangles at once. This frustum culling optimization strategy occurs prior to submitting a workload of primitives for rendering and is generally orthogonal to back-face culling and per-primitive culling that follow.

Occlusion culling

Another technique for early culling of 3D objects in large environments is occlusion culling. In essence, it attempts to identify objects that are entirely hidden behind other geometry in the scene and flag them as invisible. For occlusion culling to make any practical sense, the cost of performing it must not outweigh the time saved by not rendering the eliminated geometry. This leads graphics engines to implement at least two or all of the following strategies when implementing occlusion culling:

Simplified testing. The bounding box of each one of the objects to be validated as hidden is typically considered and conservatively checked against a proxy of geometry already rendered so far (potential occluders). The current state of the partially complete depth buffer can serve as the occluder. Modern GPUs implement special queries (occlusion queries) for this type of testing, essentially counting the pixel samples that survive the depth test.

Temporal reuse. Provided a smooth frame rate can be maintained, the visibility does not change significantly from frame to frame. This provides ample opportunity for reuse of visibility results, lazy re-evaluation and out-of-order scheduling of visibility and rendering passes. To account for fast moving objects, their bounding volumes may also be dynamically enlarged (compensating for the motion vectors) to ensure conservative occlusion queries. One way to exploit this is to use a version of the depth buffer from the previous frame, reprojected to compensate for the camera motion between frames. Another viable option is to use as occluder a quickly prepared depth buffer of the objects that were marked as visible in the previous buffer, in a pre-pass in the current frame.

Hierarchical testing. Bounding volume hierarchies (see Geometry unit) can be exploited instead of a flat set of object bounding volumes, to both cull aggregations of objects with a single operation and quickly update visibility query results up and down the hierarchy of "occludees" (bounding volumes)4.

State change minimization

A useful optimization that is orthogonal to other approaches is the minimization of graphics state changes. When emitting a work queue for processing (rendering) to the GPU, a large set of parameters must be configured, variables need to be updated, executable code has to be loaded and made ready to run and internal buffer memory has to be allocated. All these steps configure a rasterization pipeline to run in a specific way and generate a desired rendered appearance for the emitted primitives. On the other hand, chunks of geometry from the virtual environment typically have different material attributes and some times require different geometry manipulation and shading algorithms to run on the GPU to display them. For example, certain parts of the environment may be rendered as wireframe outlines, others may require solid shading or transparent rendering. Off-screen computations involving shadow generation, environment lighting or other rendering passes may also need to be prepared prior to rendering parts of the environment. All these different configurations also represent significant changes to the setup of the rendering pipeline. Arbitrarily and repeatedly modifying the graphics state whenever a particular draw call requires some change is not ideal, as it introduces significant overhead. It is therefore prudent to pre-sort the draw calls (and respective parts of the scene) according to state and avoid constant state switching. For instance, sorting renderable elements according to the shader used (see next) is a good idea. This optimization can be intuitively implemented in an entity component system5, a software architecture for developing game- and graphics-oriented platforms. Entities, i.e. objects to be (potentially) rendered may have different components, each one associated with the object’s characteristics (e.g. shadow caster, glowing, transparent), while a system, i.e. here a rendering pass requiring a specific graphics state, scans over all entities and triggers a rendering call only for those that have a compatible component attached.

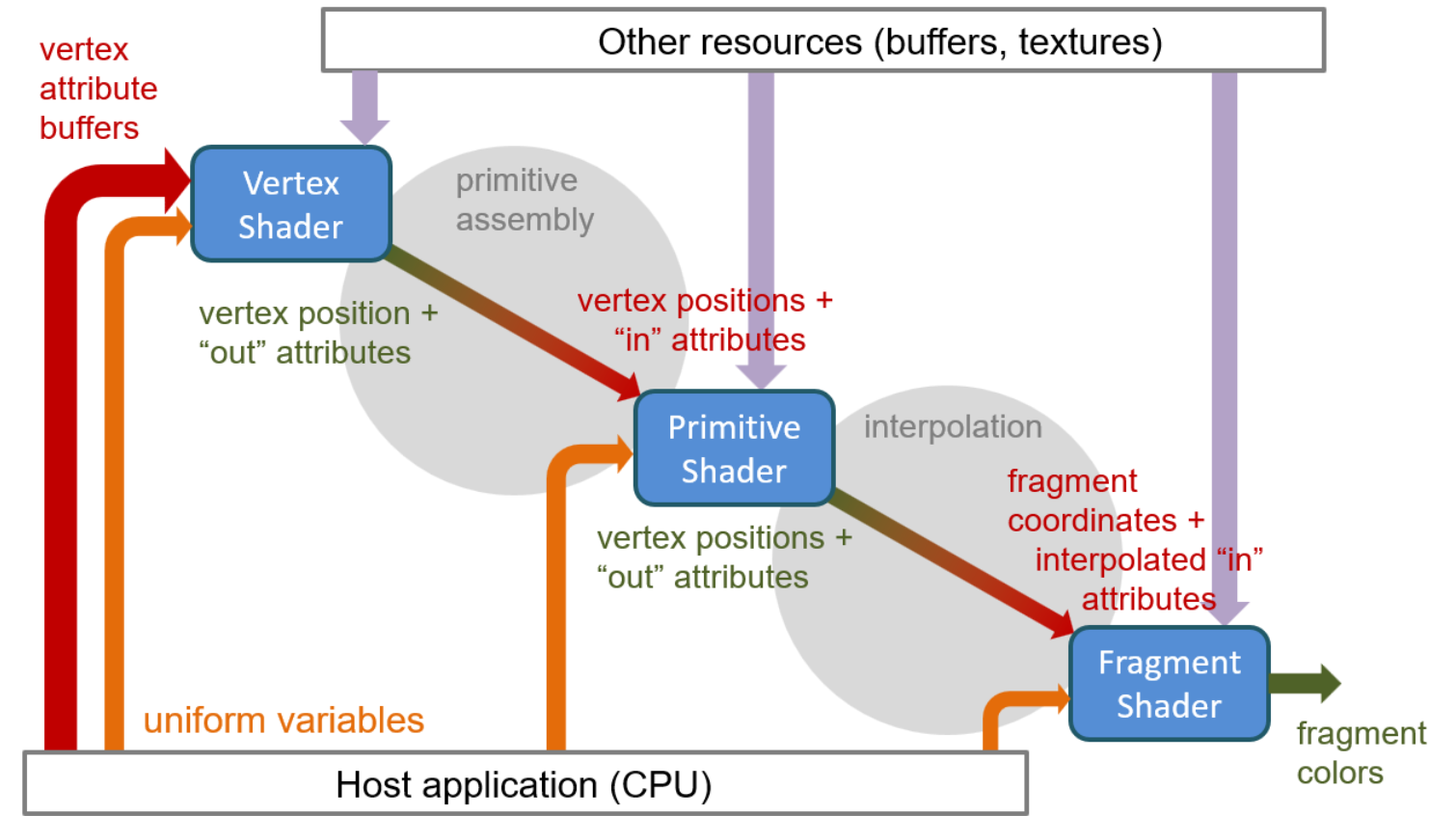

Shaders

The vertex, primitive processing and pixel shading stages are to a large extent programmable, allowing custom transformations and arbitrary vertex attributes to be computed and forwarded down the pipeline. Primitives can also be procedurally reconfigured or refined. In the programmable stages of the pipeline, shaders are executed to perform the various computations. These shaders are functions (potentially invoking other functions in their turn) with a well-defined input and output, which are written in special human-readable programming languages called shading languages, compiled into native GPU machine code by the driver’s shader compiler and linked together to form a cascade of inter-operating stages that define the specific function of the rendering pipeline.

As expected, all programmable stages of the pipeline may request random access to read resources that are potentially required by the code being executed to perform the computation. Such resources are typically image buffers that represent material textures, pre-computed data or frame buffer information produced by previous rendering cycles. Randomly accessing memory buffers for writing is also possible but not always efficient, due to the need to ensure exclusive access to memory locations during the parallel execution of the code in the GPU cores. The following simplified diagram illustrates this idea.

Shader Types

First, the pipeline is set up to work with specific pieces of machine code (the compiled shaders) that have been linked into a unified pipeline of programmable stages, the shader program. In each subsequent call to draw a set of geometric primitives (line segments, polygons, points), the attributes of each primitive vertex are passed to the vertex shader. Along with the vertex attributes, the vertex shader also has access to a number of variables, which are set by the host system and are considered immutable during a rendering call to draw a set of elements and accessible by all programmable stages. They are called uniform variables due to the particular expectation (and implemented data synchronization policy) that they cannot change between individual calls to draw elements. Uniform variables are very important for the entire shading pipeline, as they pass global variables necessary for the calculations in the programmable stages, such as geometric transformation matrices, material parameters, textures and illumination properties. In essence, every piece of information that is not part of a vertex attribute record, has to be passed to the programmable rasterization pipeline via a uniform variable in order for a shader to have access to it. The primary task of a vertex shader is to transform geometric data such as positions (mandatory) and normal or other vectors defined in local coordinates of the rendered elements to clip (normalized post-projective) space. A vertex shader optionally computes other vertex data, e.g. the position in other coordinate systems, such as ECS or WCS and repack or expand other attributes, such as vertex color information and texture coordinates.

An optional general stage that follows the vertex shader is what we call here a "primitive shader". This, depending on the specific implementation of the rasterization pipeline, can take many manifestations, from the generic geometry shader stage, to the more specific ones. such as the tesselation and mesh shaders, some of which are vendor-specific. The common underlying property in this family of shaders is that they operate on primitives, as a cluster of vertex and connectivity information, not on isolated vertices. This is useful for augmenting the primitive, e.g. subdividing — "dicing" — it into more, smaller primitives to produce finer and smoother details, replacing the geometric element type (e.g. build polygons out of point primitives to efficiently construct particles), or discarding and redirecting primitives to specific rasterization "layers".

The final mandatory stage is the fragment or pixel shader, which processes the records of the sampled points on the primitive, as these have been interpolated by the rasterizer, to produce the color, alpha value and other, complementary data to the output frame buffer(s). Typically, a single RGB+A frame buffer is allocated and bound to the output of the pipeline for pixel value writes, but this buffer representation can be extended to support more than 4 channels, by concatenating multiple rendering targets, i.e. allocated RGBA frame buffer attachments. Additionally, shaders can perform updates to random-access memory buffers resident on the GPU, but usually, specific synchronization is required to avoid overlapping the updates during parallel shader code execution. Conversely, when writing to the conventional fragment shader output frame buffer, race conditions can be more efficiently handled, since for any primitive, the generated fragments are non-overlapping in image space and primitive processing order is maintained. The primary role of the fragment shader is to compute the output color of the currently shaded pixel location. This computation can be anything from a a simple solid color assignment to complex illumination and texturing effects (see appearance unit). In this respect, it is expected that the particular shader is generally the most computationally intensive, both in terms of calculations and resource access requests (texture maps).

A Simple Shader Program

In the following two snippets of code, we present an example of a simple vertex and an even simpler fragment shader.

Let us break down the two pieces of code, written in the Open GL Shading Language (GLSL), a common shader code definition language. The vertex shader first declares the attribute binding, by stating that the first vertex attribute passed (location 0) is assumed to be the vertex position coordinates, hereafter referred to by the variable name "position" and the second attribute (location 1) is the normal vector coordinates. Both variables are three-coordinate vectors (x,y,z). Next, the shader declares that it is expecting the binding of 3 uniform variables with the specific names provided in the code, all representing and storing transformation matrix data: the geometric transformation that expresses the object-space position coordinates of the vertex in the eye (camera) coordinate system, the projection matrix that projects points to the plane and transforms them to clip space coordinates and finally, a transformation matrix for expressing directions (the normal vectors here) from object space to eye coordinates. The surface normals are passed along as input to the vertex shader and are required for shading computations in the fragment shader. The particular calculation, computes a shading value by comparing the normal vector with the camera viewing direction. If the normal vector is converted to eye coordinates, the computation is simplified and no additional "viewing direction" uniform variables need to be passed to the fragment shader. Here, for the shading that follows, we have also declared an additional output vector, n_ecs, which will carry over the result of the transformed normal vector to the interpolator and then to the pixel samples, for shading. The only function present in this particular vertex shader is the mandatory "main" function, which has a compulsory output, the gl_Position, corresponding to the clip space coordinates of the processed vertex. The vertex shader function computes the two output vectors (clip space position and eye space normal) by applying the appropriate sequence of transformation matrices and doing the necessary vector conversions.

// Vertex shader.

#version 330 core

// vertex attributes used by the vertex shader.

layout(location = 0) in vec3 position;

layout(location = 1) in vec3 normal;

// uniform variables accessed by the shader.

uniform mat4 M_obj2ecs; // "modelview" matrix: local object space

// coordinates to eye coordinates transformation

uniform mat4 M_proj; // projection matrix

uniform mat3 M_normals; // inverse transpose of the upper-left 3x3 of the

// modelview matrix

out vec3 n_ecs; // optional output of the vertex shader:

// Normal vector in ECS coordinates.

void main()

{

// compulsory output: the normalized clip-space coordinates of the

// vertex position

gl_Position = M_proj * M_obj2ecs * vec4(position, 1.0);

// eye-space (camera) coordinates of the normal vector.

n_ecs = M_normals * normal;

}// Fragment shader.

#version 330 core

// Optional sampled attributes

in vec3 n_ecs; // the interpolated normal vector computed in the

// vertex shader.

out vec4 frag_color; // The shader output variable (RGBA)

void main()

{

// Simple shading: maximum lighting when normal faces the camera (+Z)

vec3 n = normalize(n_ecs); // Interpolated normals are no more of

// unit length. Must normalize them.

// Simple diffuse shading with virtual directional light

// coming from the camera. Assume a red surface color: (1,0,0)

vec3 color = vec3(1.0, 0.0, 0.0);

float diffuse = max(n.z, 0.0);

frag_color = vec4(color*diffuse, 1.0);

}In the fragment shader of this example, where the pixel sample records end up after interpolation of the primitive attributes by the rasterizer, there are a number of compulsory input data that are passed, including the fragment coordinates. The user-defined additional output of the vertex shader is interpolated along with the mandatory attributes and declared here as input (in vec3 n_ecs). In the main function (the only function in this code), the normal vector is first normalized, since linear interpolation does not retain the unit length of the shading normal, if different at each vertex. Then, the shading is computed by assuming a light source positioned directly at the camera: We take the dot product between the normal vector and the eye direction (positive Z axis in eye space coordinates). This corresponds to the cosine of the angle between two directions and translates to diffuse shading radiance flow. Fortunately, in this case, since we have converted the normal vector to eye space coordinates in the vertex shader, the dot product is simplified, since = = . To avoid negative values for flipped polygons, the shading is also clamped to zero. Finally, the output color is the shading coefficient multiplied by the base color of the surface (here we do not use a physically-correct model). The alpha value of the output fragment is always 1.0 in this example, signifying an opaque primitive or, more generally, one with maximum blending presence.

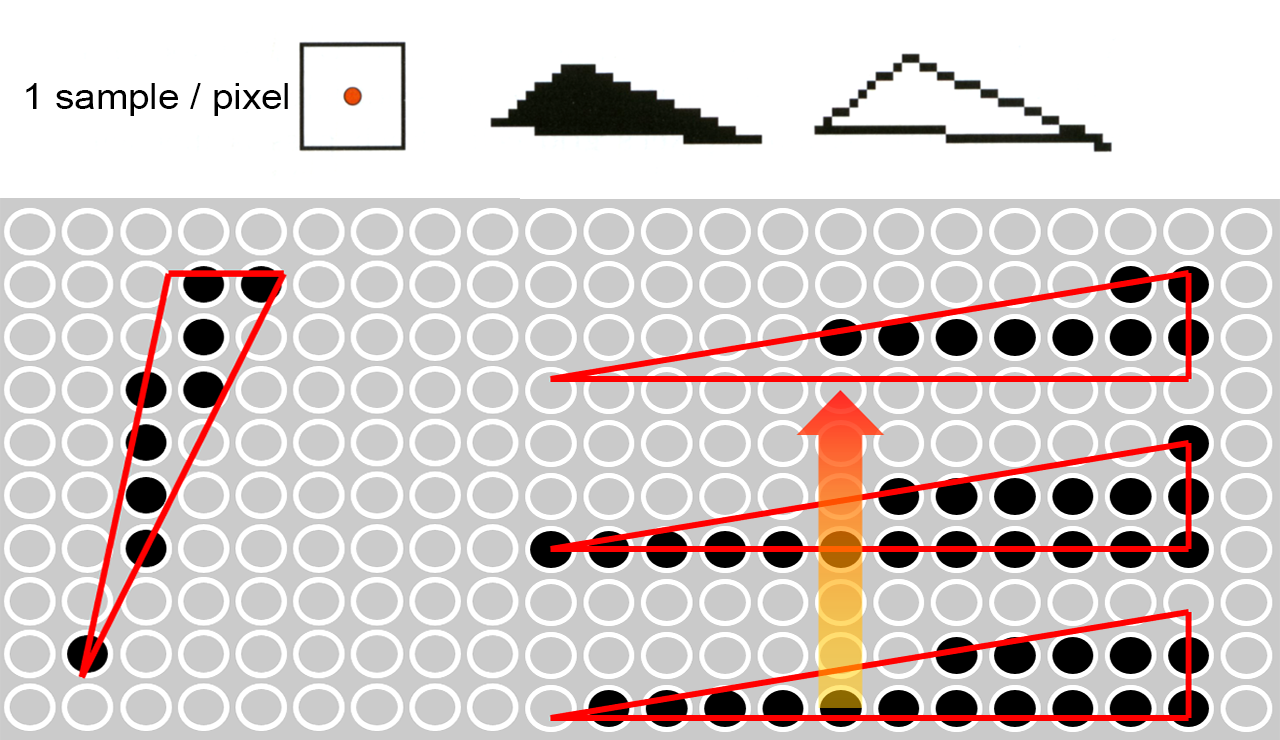

Antialiasing

During the rasterization step, where image samples are drawn and a decision is taken regarding the inclusion of this sample or not inthe set of pixel samples to be forwarded for shading, this decision is so far binary: The pixel sample is either retained, as belonging to the primitive, or rejected, as not being part of the primitive. Yet, this decision is based on a particular sampling of the image raster with a specific (fixed) sampling rate, dependent on the image resolution. For samples at the boundary between the "interior"6 of the primitive and the background, this binary decision introduces aliasing, since there is no practical frequency that can effectively sample and reconstruct an abrupt transition from the interior to the exterior of the primitive. In practical terms, we can never display a primitive correctly, in the strict, mathematical sense, unless its border is either vertical or horizontal and exactly coincides with the midpoint between two columns or rows of pixels, respectively. We can only approximate its shape with a varying degree of success. Now going back to our one-sample-per pixel rasterization mechanism, turning a pixel on or off for a primitive with full or no pixel coverage, respectively, invariably creates a pixelized look to the rendered primitives. Worse, for thin structures, entire primitives may be under-sampled or even completely missed.

Since we cannot raise the sampling rate of our image beyond what the target resolution can offer, we have to resolve to various band-limiting (low-pass filtering) techniques to "smooth" the rendered primitives. The prevailing techniques in computer graphics are all in the post-filtering domain, using multiple samples at a higher spatio-temporal rate and then averaging the result to conform with the particular single frame resolution. This does not mean that there are no pre-filtering methods in the literature, but they tend to be too specialized to be practical. We present below some of the most common types of antialiasing techniques.

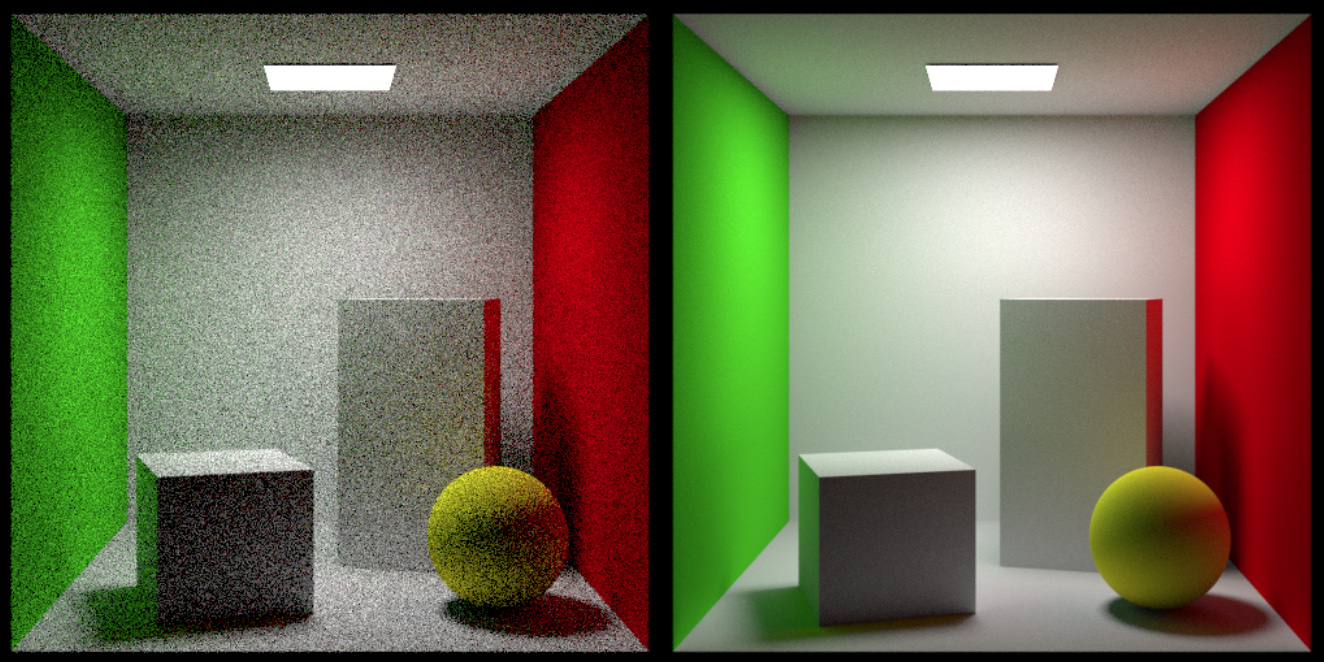

Super-sampling (SSAA)

Supersampling can be considered a brute-force way to mitigate the insufficient resolution of the raster grid, but in no way can it solve the aliasing problem. In essence, it allows to extend the native sampling rate to correctly capture higher frequencies and then subject the resulting signal to a low-pass filter operator to adjust the signal to the maximum attainable frequency of the actual image. In other words, yes, supersampling can improve the fidelity of the image, by smoothing transitions and more accurately representing sub-pixel features, but practically only mitigates the problem to even smaller details. The most important drawback of supersampling comes from the fact that it literally multiplies the actual samples taken on the raster plane, increasing the number of containment tests and shading operations proportionally to the oversampling rate. For instance, quadrupling the number of image samples (4 samples per pixel), results in 4 points being tested for containment and the resulting active samples being all shaded. The resulting shading values are then averaged. Keep in mind that in the case that not all pixel samples are validly contained within the primitive’s effective area, the coverage of the pixel is not 100%. Instead, the ratio of the contained sub-pixel samples over the total sub-pixel samples are considered as the "presence" of the pixel, establishing the amount of partial occupation of the pixel by the primitive. This factor is used to properly blend border pixels with the contents of the frame buffer.

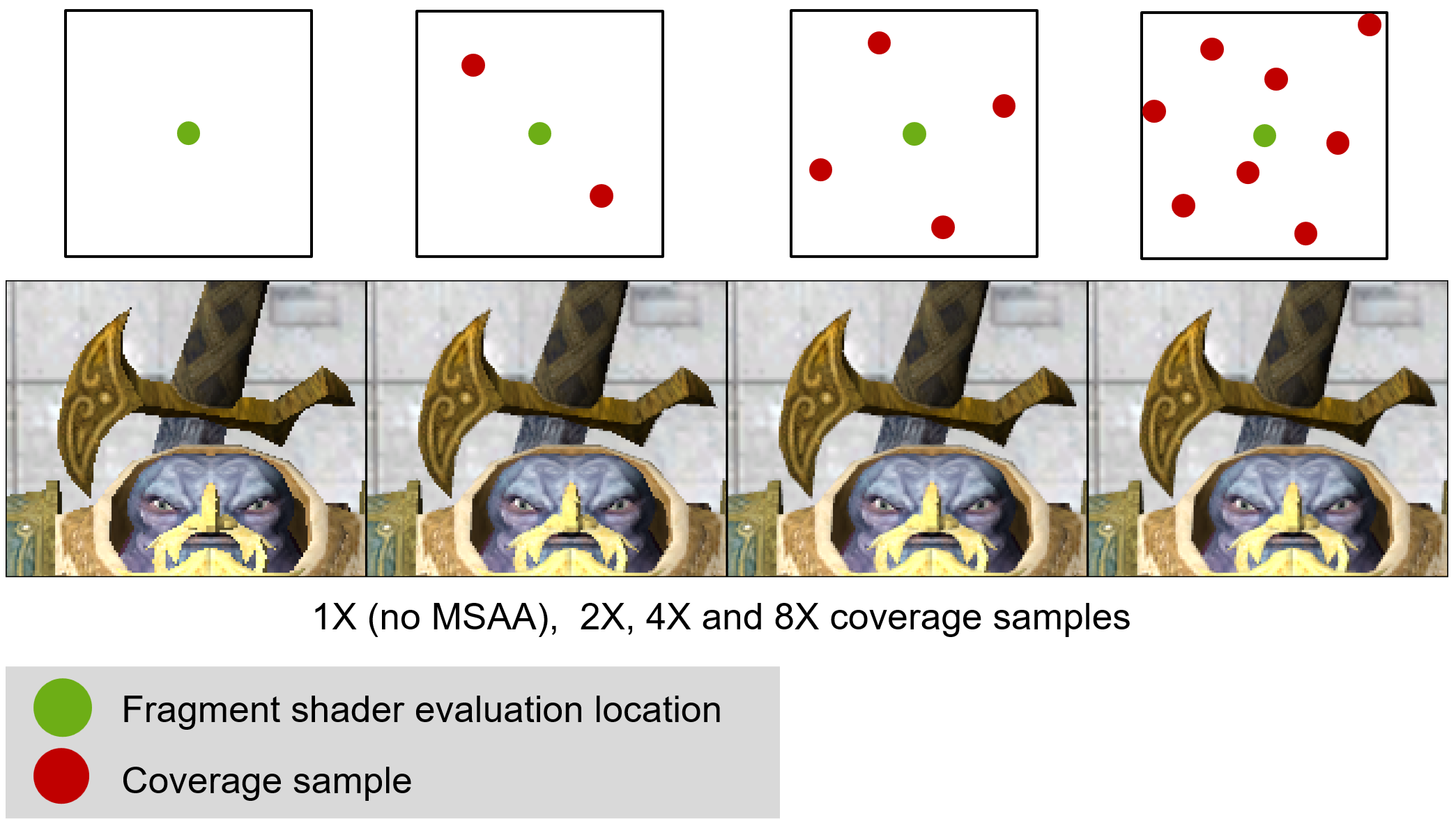

Multi-sampled Antialiasing (MSAA)

Although SSAA is quite effective in smoothing the image, it is also very expensive, since the shading computations are multiplied by (up to7) the super-sampling factor. To avoid the overhead, a trade-off has been devised: instead of evaluating shading for all sub-pixel samples, a single sample is used for shading computation and the rest are only used for determining the pixel coverage. The pixel coverage only involves the primitive containment testing method, which is very fast to evaluate by the rasterizer, while the cost of shading is the same as not performing antialiasing at all. This technique, which has been implemented in GPU hardware from simple mobile GPUs to desktop ones, is called multi-sampled antialiasing (MSAA) to differentiate the approach from the brute-force SSAA. However, MSAA trades accuracy for speed since: a) it only evaluates 1 sample, inheriting any shading-induced aliasing artifacts, such as shadow determination artifacts and specular "fireflies" and b) the exact point to use for shading may not be representative of the cluster of the coverage samples. It is possible to determine a good shading evaluation position (e.g. the cover sub-pixel samples average location), but with some additional cost.

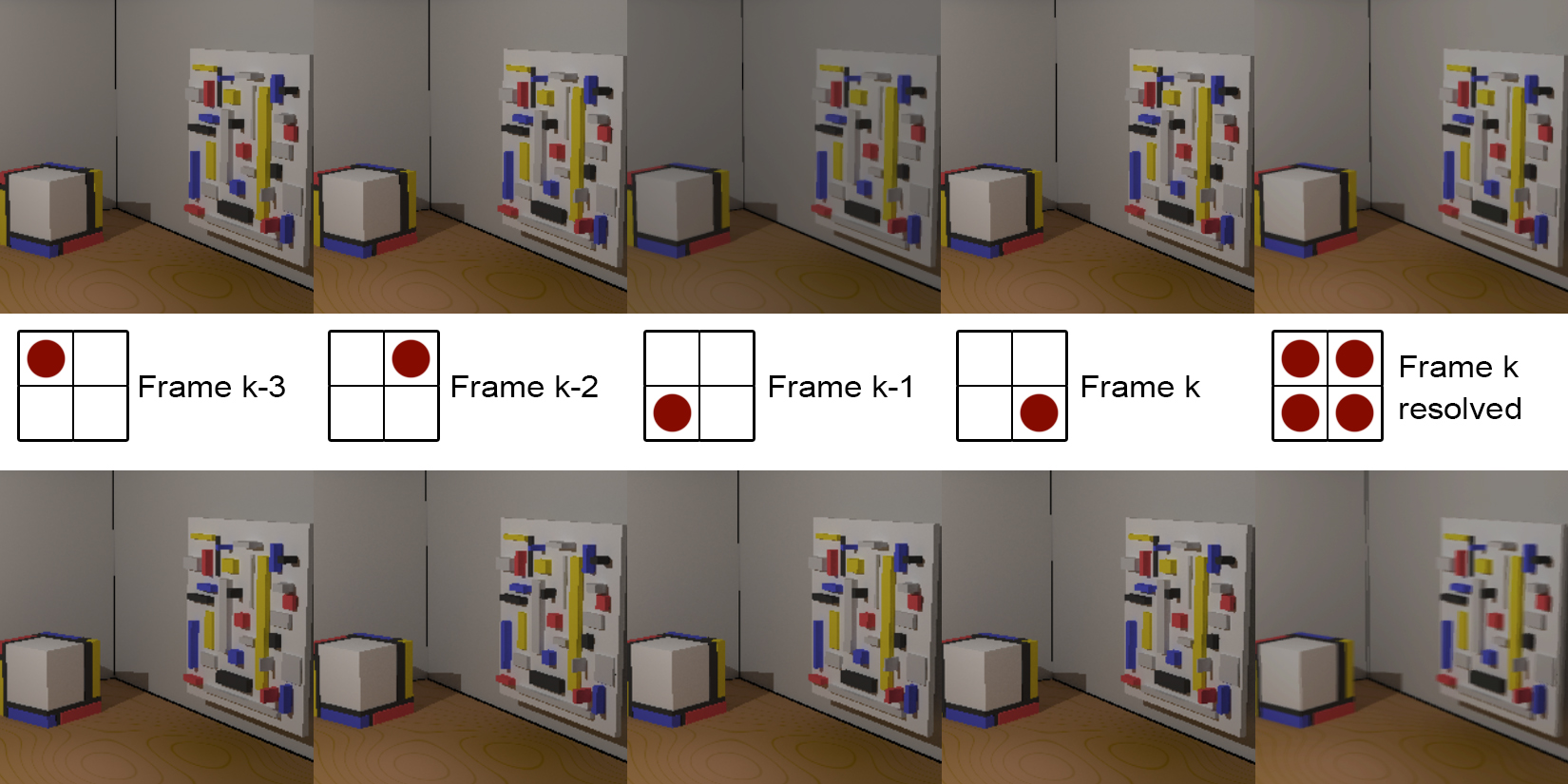

Temporal Antialiasing (TAA)

Temporal antialiasing is a special form of super-sampled antialiasing that instead of only spatially distributing the samples over the pixel area, in instead uses a spatio-temporal distribution, spreading samples across time by using sample positions from previous frames to amortize the cost of computing all sub-pixel samples (and shading) for a pixel in the same frame. To resolve the antialiased image in frame , the frame buffer contents of the previous frames are also re-used. In a simple implementation, as shown in the following figure (with ), a different sub-pixel sampling location is used in every frame, which can by repeated every frames. allocated buffers are used, averaging the current frame with the previous frames to obtain a resolved antialiased image. The accumulated values of previously generated frames can also be used instead in a running average with an exponential decay, to save frame buffer memory. This simple technique is valid and effective if the contents of the image remain stationary. However, if there is animation involved (as in the bottom row of the figure), ghosting artifacts appear. One way to avoid this is to enable the blending only when small no significant motion is present, e.g. when the camera is not moving. Another and far better way to address the motion issue is to compensate for it. The image-space motion field is stored in a specially prepared velocity buffer (two scalar values per pixel), computed during normal rendering of frame or via an optic flow estimator, external to the rendering engine. The velocity vectors are then used to re-project every pixel to an estimated position in the previous frame(s). The color stored in that location is then used in the averaging operation.

Deep-learning Antialiasing Approaches

In the case of temporal antialiasing, to avoid ghosting artifacts, hand-crafted heuristics had to be used to correct problems that resulted from motion in the image, such as clamping and velocity field-based re-projection for motion compensation. With the advent of deep-learning and specialized hardware to accelerate the evaluation of neural network models (tensor cores), it became evident that small learned neural models can effectively replace the work of designed heuristics, given the same input. Since aliasing is tightly coupled with insufficient image-domain sampling, learning-based antialiasing approaches helped tackle at the same time the problem of antialiasing and image upscaleling, leveraging known ideas from super-resolution imaging, by using multiple frames to reconstruct not only a a higher-fidelity image but also a higher resolution one, not unlike TAA.

Transparency

Transparency in rasterization should not be confused with the permeability of real surfaces and the transmission of refracted light through the mass of objects. Although energy distribution between reflected and transmitted components can be accurately modeled at the interface of objects (the surface) and all physically-based models for local illumination are applicable to surface rendering, in simple rasterization, there is no notion of a volume of an object for light to traverse. Remember that rasterization treats every elementary primitive as a standalone entity, computing local lighting in isolation, and that rasterized primitives are not necessarily surfaces in 3D space. Rasterization, i.e. the process of converting a mathematical entity into ordered samples, encompasses also points, lines, curves in 3D and their counterparts in 2D. We basically treat transparency as a blending factor, determining the presence of a primitive when combined with other rendered parts. It is possible, to approximate to some extent the appearance of physical (solid) objects via various multi-pass approaches, heuristic algorithms and the help of provided textures, but a simple single-pass drawing of polygons cannot achieve the effect. Nevertheless, transparency, in a non-physical sense, is an important visualization tool, helping us visually combine overlapping geometric elements, blend shapes to produce new forms, create artificial lighting or even in some cases, perform elementary filtering tasks.

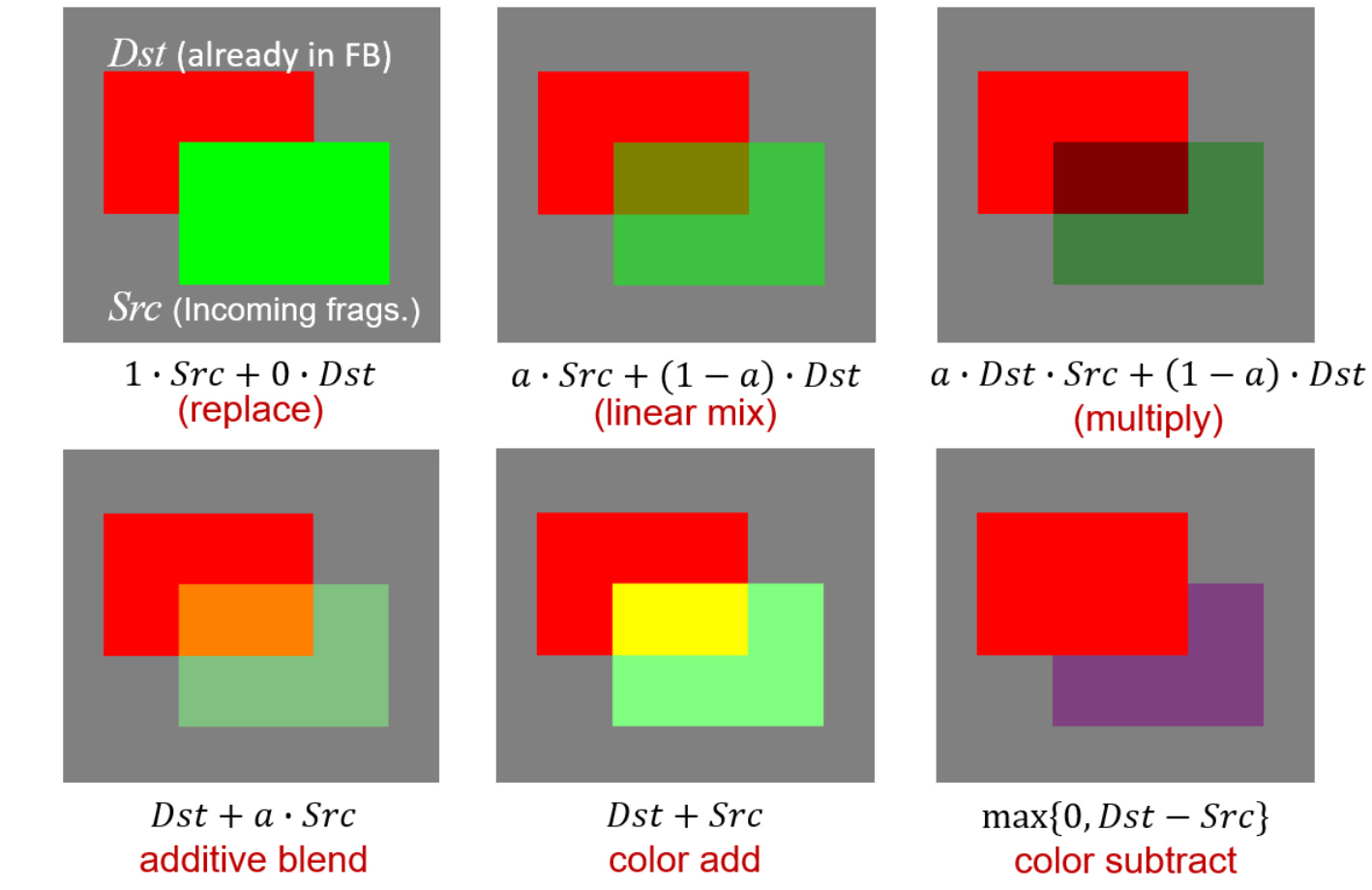

Handling Transparent Objects

Transparent primitive rendering involves two elements: a) the definition of an alpha value for the pixel sample within the fragment shader and b) the specification of a blending equation to be used uniformly for the current rendering pass. The latter specifies how the alpha value is used in conjunction with the already accumulated color and alpha values. Graphics APIs provide specific calls to set up the blending equation, including how the alpha values are weighted and what operation to perform between the source (the current) fragment and the destination (the existing) pixel values. Some examples of blending operations are shown in the next figure:

The presence of a colored fragment in the final frame buffer is not only affected by its alpha value, however. The pixel coverage computed during primitive sampling is also used, linearly modulating the final mixing of the result with the frame buffer, regardless of the blending function used, since it represents "what portion" of the existing pixel is changed, without caring "how" the changed portion is affected.

It is important to understand that for most blending operations the order of primitive appearance in the drawing call queue is important; since the mixing of the source and destination values happens right after a fragment color and alpha value have been computed by the fragment shader, a "source" fragment becomes the "destination" value if the order the two primitives are rasterized is reversed. Certain operations are of course unaffected, such as pure additive blending, but in most other cases, different, order-dependent results occur. This is demonstrated in the following figure. The most significant implication of this is that the same object, without any alteration in its topology or primitive ordering will appear different under different viewing angles, since the order the fragments are resolved is not determined with respect to the viewing direction, e.g. back to front with respect to the eye space Z axis.

Furthermore, transparent rendering clashes with the simple hidden surface elimination method of the Z-buffer algorithm, as demonstrated below. In this simple example, two polygons are drawn with the depth test enabled in the GPU pipeline. In the left example, the transparent green polygon is drawn first. The depth buffer is cleared to the farthest value, so every pixel sample of the green polygon passes the test and is shaded. According to its alpha value, every fragment is blended with the gray background, as expected. But then arrives the red polygon, whose depth is farther from the green one’s. When attempting to rasterize the polygon, all pixel fragments that overlap on the image plane with the green polygon fail to pass the depth test and are rejected before having any chance to be (even erroneously) blended with the existing colors. On the other hand, if the red polygon came first, the depth resolution order would not cull the fragments of the part of the red polygon that is obscured by the green one, allowing this area to be blended and visible behind the green semi-transparent element.

Both problems are serious, especially when multiple transparent layers need to be drawn. One option to avoid entirely rejecting geometry behind transparent layers is to crudely sort the geometry into two bins and perform a separate pass for opaque and transparent geometry. Opaque elements are drawn first, proceeding as usual, with the depth testing and depth buffer updates enabled. This makes sense as the opaque geometry definitely hides all other geometry behind it, transparent or not. Therefore, if the closest opaque surface samples registered in the depth buffer are in front of any upcoming transparent fragments, the latter must be culled. Then in a second pass, all transparent geometry is rendered, but with a twist: depth testing is enabled, to discard transparent fragments behind the already drawn opaque geometry, but depth updates are disabled, so that no transparent fragment can prevent another transparent sample to fail the depth test because of it, regardless of the order of display. Needless to say, the order of appearance of the transparent fragments still affects the final blending result and transparency resolution is still order- and view-dependent. However, now we have contained the problem to transparent elements only.

Order-independent Transparency

To correctly draw transparent layers of geometry, surface samples must be first sorted according to image/eye/clip-space depth and then blended together from back to front, using the blending function activated, the each fragment’s alpha value and the respective coverage. This is exactly what the A-buffer (anti-aliased, area-averaged, accumulation buffer) algorithm does (Carpenter 1984), which has been around for many decades, even before the dawn of the rasterization architecture as we now it. Instead of storing a single (nearest) depth value, it maintains a list of all fragments intersecting a pixel. In modern instantiations of the method, each record of the sorted list contains the computed fragment color, depth, alpha and pixel coverage values. After drawing all elements, the list attached to each pixel is sorted (can be also sorted during fragment insertion) and the pixel color is resolved. In the original algorithm, whose primary concern was memory compactness and early termination, dealing mostly with opaque, antialiased geometry, the pixel resolve stage traversed the list front to back, maintaining a mask of "active" subpixel samples to resolve. When all sub-pixel samples were fully-covered, traversal was interrupted. Since nowadays an A-buffer implementation is primarily used for correctly handling transparency, the list is traversed back to front, blending the current fragment with the result of the blended, underlying ones.

The A-buffer technique is a lot more expensive than the simple Z-buffer method, as it involves, dynamic lists, more data per fragment and requires some sorting mechanism. A GPU implementation of the original method, using per-pixel-linked lists is possible, if one can guess how much memory needs to be (pre-) allocated, before running the algorithm. Unlike CPU memory, on-the-fly dynamic video memory allocation is not allowed and a quick fragment counting rendering pre-pass is typically used to record the amount of memory needed for the A-buffer. If this is to be avoided for performance reasons, either a very conservative budget is used (which is never ideal), or a clamped list is considered per pixel, storing up to fragment records, instead of an arbitrarily large number of them. Alternative multi-fragment rendering approaches also exist, that do not necessarily maintain an actual list and/or perform sorting on the fly (e.g. depth peeling). A comprehensive discussion about order-independent transparency (OIT) and the various multi-fragment rendering techniques to address it can be found at (Vasilakis, Vardis, and Papaioannou 2020):

Deficiencies of Rasterization

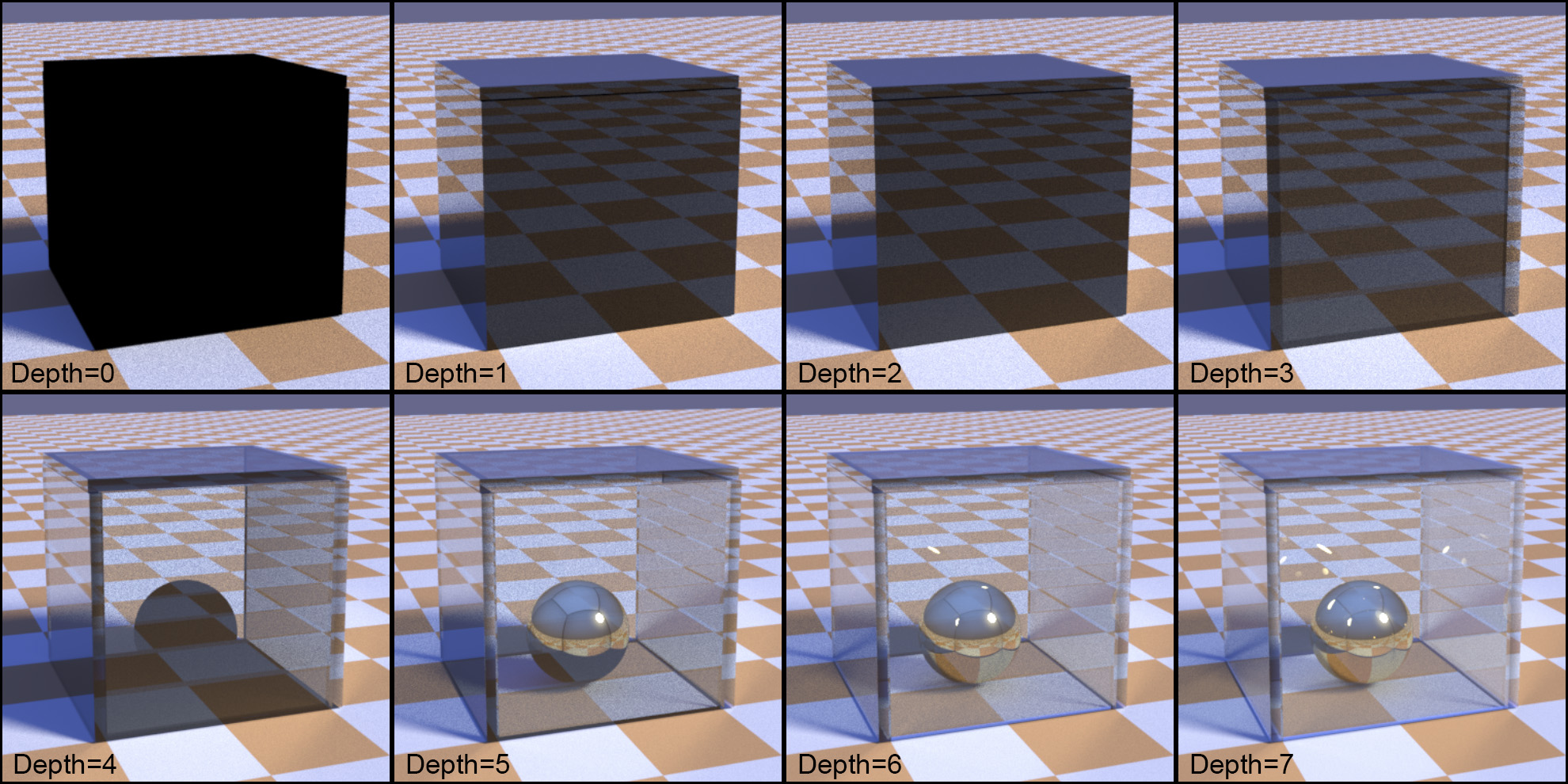

Rasterization is a very straightforward, fast approach to rendering and the basic pipeline operates in a divide and conquer strategy, rendering geometry in batches (draw calls), each primitive of a patch being processed independently, then each sample of a primitive being shaded independently. This enforced isolation makes the rasterization architecture extremely efficient and highly parallel, eliminating the need for global access to (and maintenance of) geometric data, as well as complex synchronization and scheduling on the hardware implementation. However, this narrowing of data visibility as information travels down the pipeline is also responsible for the many limitations of the basic rasterization method. Requiring vertex, primitive and pixel sample independence at each pipeline stage, means that these stages must be agnostic of other scene data; a vertex cannot access other vertices, a fragment shader cannot access other pixel samples but its own, a polygon is processed not knowing the full geometry of an object. This local-only access, prevents most algorithms that depend on global scene information to be applied within a shader. For example, when coloring triangle fragment, we can pass the light position and other attributes as uniform variables, but we have no way of determining whether the light sampled from the fragment’s position is intercepted by other geometry, causing a shadow to form. Things can become significantly worse if general global illumination is desired, where outgoing light depends on the incoming light from other surfaces, as is the case of reflected and refracted light.

To overcome such visual limitations of rasterization, in computer graphics we either abandon the rasterization architecture for the more general rendering approach of ray tracing (see further below in this unit), or resort to generating and maintaining auxiliary data via one or more preparatory rendering passes, which typically encompass the approximate and partial representation of the scene’s geometry, in order to make this information available during visible fragment shading. A prominent example of this is the shadow maps algorithm, detailed below, which enables the approximate yet fast light source visibility determination within a fragment shader. Another solution to the problem of indirect lighting is the use of pre-calculated information in the form of textures, such as environment maps and lightmaps (see next).

Simple "direct" rasterization of surfaces can also be inefficient when the depth complexity increases (many surfaces overlap in image space), since many shading computations may be waster to render fragments that are later overridden by samples closer to the viewpoint. Another issue stems from the lighting computations. Multiple light sources require either iterating over them inside the fragment shader, which introduces a hard, small limit on their number, or re-rendering the full scene once per light source, which is very costly. Furthermore, the rasterization of very small primitives, i.e. pixel- or sub-pixel-sized ones, incurs a penalty during the sampling process. The rasterizer, in order to compute necessary values to draw textured primitives (at least, the texture coordinate image space derivatives), rasterizes primitives in small pixel blocks and computes interpolated values for the samples even if these are not forwarded for display and shading. For small primitive footprints on the image, out-of-boundary samples will be evaluated often, which will be also subsequently re-evaluated for the neighboring primitives. Furthermore, the GPU hardware is optimized for processing few triangles with many pixel samples at a time, not the other way around. This has led graphics engine developers to seek ways to bypass the standard, fixed sampling system of the GPU for small geometry, implementing a software-based rasterization stack as a general-purpose compute shader that runs alongside conventional hardware rasterization8.

Rasterization-based Techniques

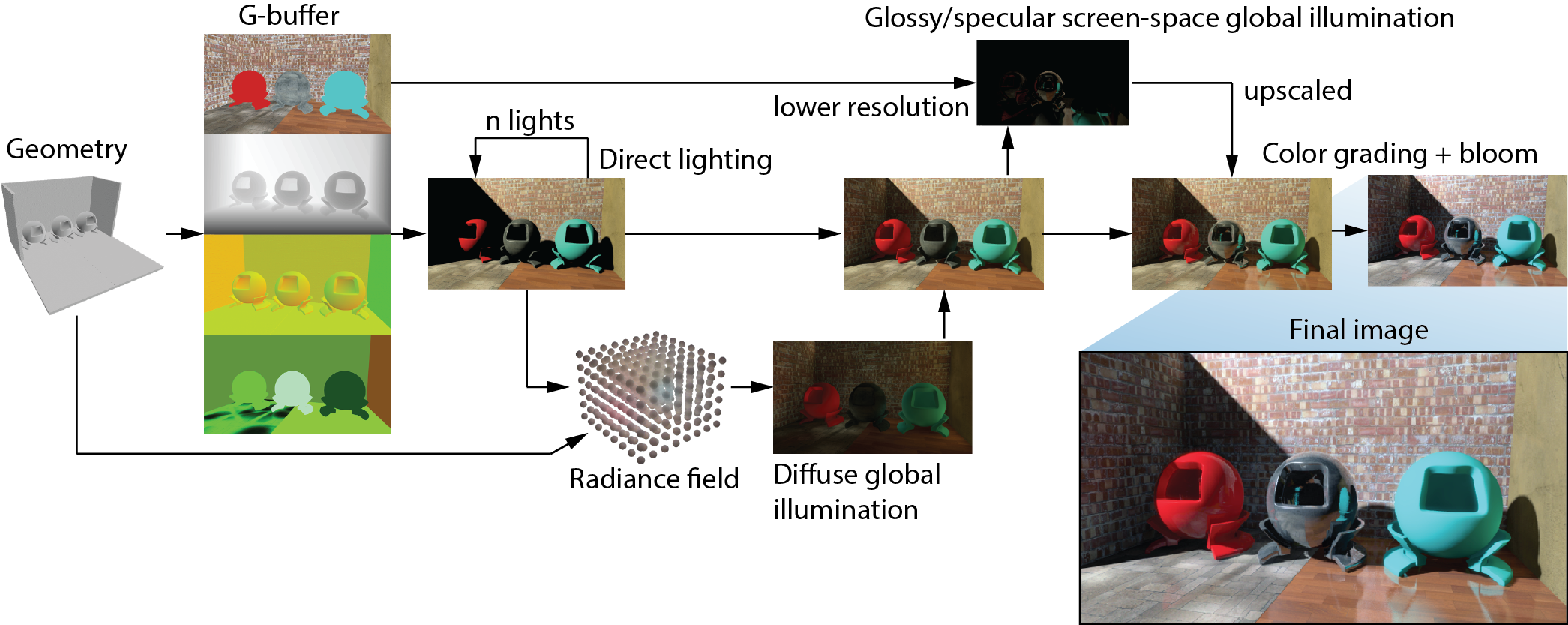

In this section, we present some important ideas and approaches to augment the capabilities of the basic direct rasterization architecture. A key element in most cases is the fact that the rendering of a complete frame needs not be done in a single drawing pass. Multiple passes can be used to prepare intermediate results and auxiliary image buffers that contain illumination and geometry information that can be exploited by a "final" pass to draw a picture with higher fidelity, support for more phenomena or increased drawing performance. The simplest such example is the two-pass approach to separately draw opaque and transparent geometry, as discussed above. In most cases, this process is not relevant to image compositing, as the intermediate buffers often convey information that is different in nature or coordinate system than the main pixel coloring pass. For example, one pass may prepare a sampled version of the scene as observed from the point of view of a light source (see shadow maps algorithm), or produce buffers of geometric attributes (see deferred rendering). Needless to say, most modern graphics engines implement multi-pass rendering with many different stages, combining results in a non-linear stage graph, often re-using partial results of previous frames as well or amortizing their creation across several frames.

Deferred Shading

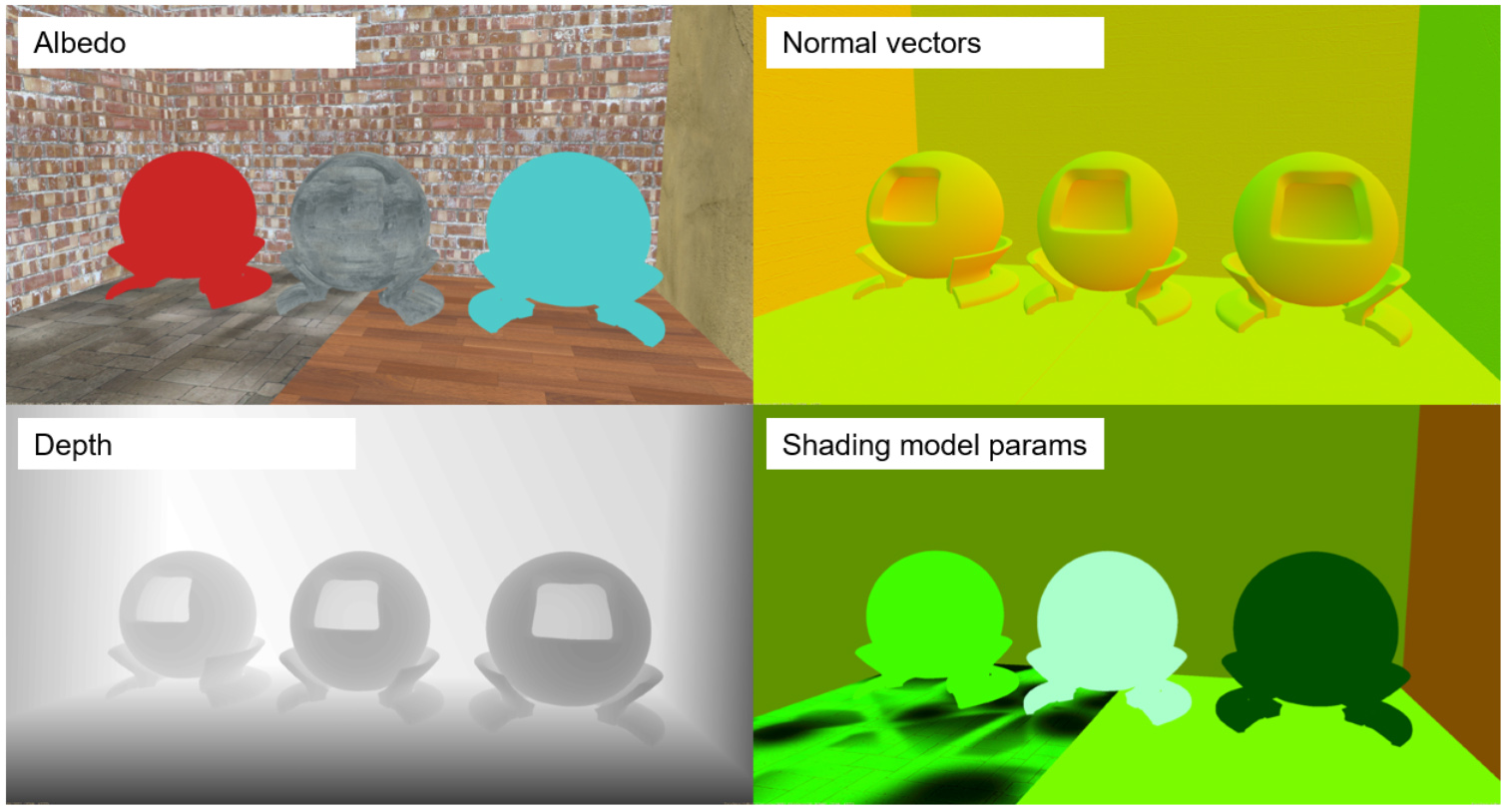

Deferred shading is a rasterization-based software architecture that was invented to address the problem of wasted and unpredictable shading computation load due to pixels being overwritten during hidden surface elimination. It delays (defers) shading computations until all depth comparisons have been concluded, performing shading only on truly visible fragments. To do this, deferred shading is divided in two discrete stages: the geometry pass and the shading pass. In the geometry pass, a number of image buffers are bound and recorded, collectively comprising the geometry buffer or G-buffer, all in one pass, with each channel containing a particular piece of geometric or material information. Apart from the default depth buffer enabled and prepared as usual, this information may include basic shading information, such as the RGB albedo, normal vector, metallicity, roughness and reflectance at normal incidence. The position and orientation of each fragment can be easily recovered in any global coordinate space (clip space, eye coordinates, world coordinate system) using a transformation matrix and the registered pixel location and depth, to perform shading computations in the next step. Additionally, other data may be also written in the G-buffer, such as interpolated velocity vectors, eye-space depth, emission, etc.

The shading pass is performed in image space, completely dispensing with the scene representation. The G-buffer attributes include all necessary information to run a local shading computation per pixel. To implement the shading pass, a quadrilateral covering the entire viewport is rasterized, and its fragment shading invocations are used to evaluate the shaded pixel, fetching the corresponding data from the G-buffer. Illumination from multiple sources can be implemented again inside a loop running in the lighting sub-pass, but also using separate draw calls per light. Now the second option is rather fast, as essentially two triangles are drawn per call. Furthermore, the area of effect of light sources has an often limited footprint on screen, facilitating the use of a different proxy geometry to trigger the lighting computations, further reducing the shading cost, as pixels guaranteed to be unaffected by the current light source are never touched.

The main benefits of deferred shading are the following:

Known and fixed shading cost, regardless of scene complexity. Shading budget is only dependent on image resolution, since only visible fragments get shaded.

Random global access to image-space geometric and material attributes of other visible fragments. This enables the implementation of many important screen-space algorithms to do non-local shading and filtering.

Ability to decouple the computation rate for different rendering passes over the G-buffer (decoupled shading). For example, lighting can be computed at 1/4 the resolution of the G-buffer, while screen-space ray tracing or bloom effects can be computed at an even lower resolution and then up-scaled.

However, there are certain limitations that come with the decoupling of the geometry rasterization and the shading. First of all, since only the closest (according to the depth test) fragments survive the geometry pass and record their values in the G-buffer, it is impossible to support transparency in deferred shading. For this reason, in practical rendering engines, deferred shading is performed for opaque geometry, which typically comprises most of the virtual environment, and transparent geometry is rendered on top of the prepared, lit result using as a separate direct (immediate) rendering pass. Transparent geometry is culled according to the prepared depth buffer of the opaque geometry, as usual.

The second limitation involves antialiasing. Certain techniques, an especially MSAA, are rendered useless with deferred shading, as they can only be applied to the geometry stage. Lighting is not antialiased. This is one of the reasons why MSAA has lost ground in practical game engine implementations, in favor of alternative, image-space techniques, which not only are compatible with the deferred shading pipeline, but also take advantage of the additional geometric and material information available through the G-buffer, to improve the filtering quality.

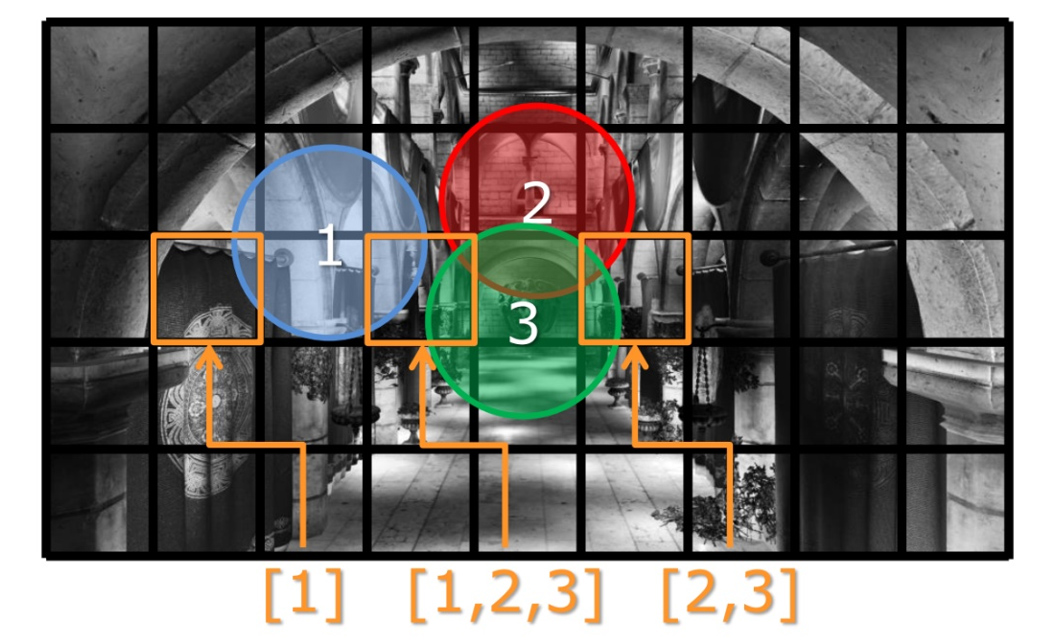

Tiled and Clustered Shading

Tiled rendering is a technique orthogonal to deferred shading. Its primary purpose is to limit the resources required to be accessed at any given time during rendering and is manly used to bound the number of light sources that affect a particular part of the image, in scenes with too many lights to iterate over efficiently. Tiled rendering, as the name suggests, splits the image domain into tiles and renders each one of them independently, after determining which subset of the shading resources truly affect each tile. A simple example is given in the following image. In this particular example, let us assume that the scene contains too many lights to be efficiently iterated over within a single pixel shader. So the pixel shader can only handle at most 4 light sources. We also make the assumption that most of the light sources are local and with low intensity, meaning that they have a limited range within which they practically contribute to any visible change in the scene’s illumination level. If we rendered the entire viewport at once, all light sources should have been accounted for. Failing to do so, by limiting the rendering pass to 4 sources, would mean that either we would need to cull a very high number of potentially important light sources, or repeat the lighting pass, until all quads of lights have been processed. When using tiled rendering, the projected extents (disk) of each source can be tested against the tiles’ bounding box. An array of up to 4 light sources can be created then for each tile separately, allowing the contribution of a higher number of light sources to the image, spatially distributed among different image tiles, at (nearly) the same total image buffer generation cost as a single 4-light rendering pass.

https://media.gdcvault.com/gdc2015/presentations/Thomas_Gareth_Advancements_in_Tile-Based.pdf.

Clustered shading is a generalization of the above stratification approach, were instead of considering a subdivision of the 2D image plane, tiling is applied to the three-dimensional space, usually the clip space. In this sense, a finer control of importance is possible and fewer resources are enabled per tile. Importance can be now tied to the distance to the camera position, meaning that for far away tiles along the Z tiling direction, different limits can apply. For example, for volumetric tiles closer to the viewpoint, one can accept more per-tile light sources to be rendered, reducing them or completely disabling them for distant tiles.

Tiled Rendering

Tiled shading is not not be confused with tiled rendering. Tiled rendering is a more drastic modification of the rasterization pipeline to directly operate on one image tile of the full frame buffer at a time, right from the start. The idea is to reduce the (hardware) resources required to produce a complete high-resolution frame buffer, by working on one smaller region at a time, requiring a fraction of the memory for all tasks (working output pixel buffer, attribute and fragment queues). Tiled rendering treats each tile as a mini frame buffer for the purposes of clipping. Primitives are split at the boundaries and their parts forwarded to the corresponding tile queues for rasterization, to avoid re-sampling polygons overlapping multiple tiles.

A beneficial side-effect of concentrating the effort of the software or hardware implementation of such a tiled architecture to a spatially coherent region is that data caching efficiency is drastically improved and flat in-tile shared memory access is now practical. As a consequence, tiled rendering is widely used in mobile and console GPU implementations, but also in desktop GPUs.

Decoupled Shading

Deferred shading is one form of decoupled shading in the sense that it separates the shading computational load from the complexity of the drawn geometry. Other forms include statically or adaptively decoupling the image resolution from the actual shading rate and texture-space shading. In the first form, shading occurs at a lower resolution internal frame-buffer and the prepared result is then upscaled to match the desired output resolution. Here, one of two things can be happen: a) Perform only specific expensive pixel shading calculations (e.g. glossy reflections) in low resolution and then upscale only these effects to the native resolution, maintaining a different rate for each shading calculation. b) Render the entire image at a lower resolution and predict an upscaled version of it. The latter, which is based on theory and methods related to super-resolution video, relies on designed or learned predictors, typically using neural networks (see for example NVIDIA’s DLSS), to exploit previous frames and G-buffer information alongside the low-resolution frame buffer, to derive a well-informed high-resolution version of the current frame.

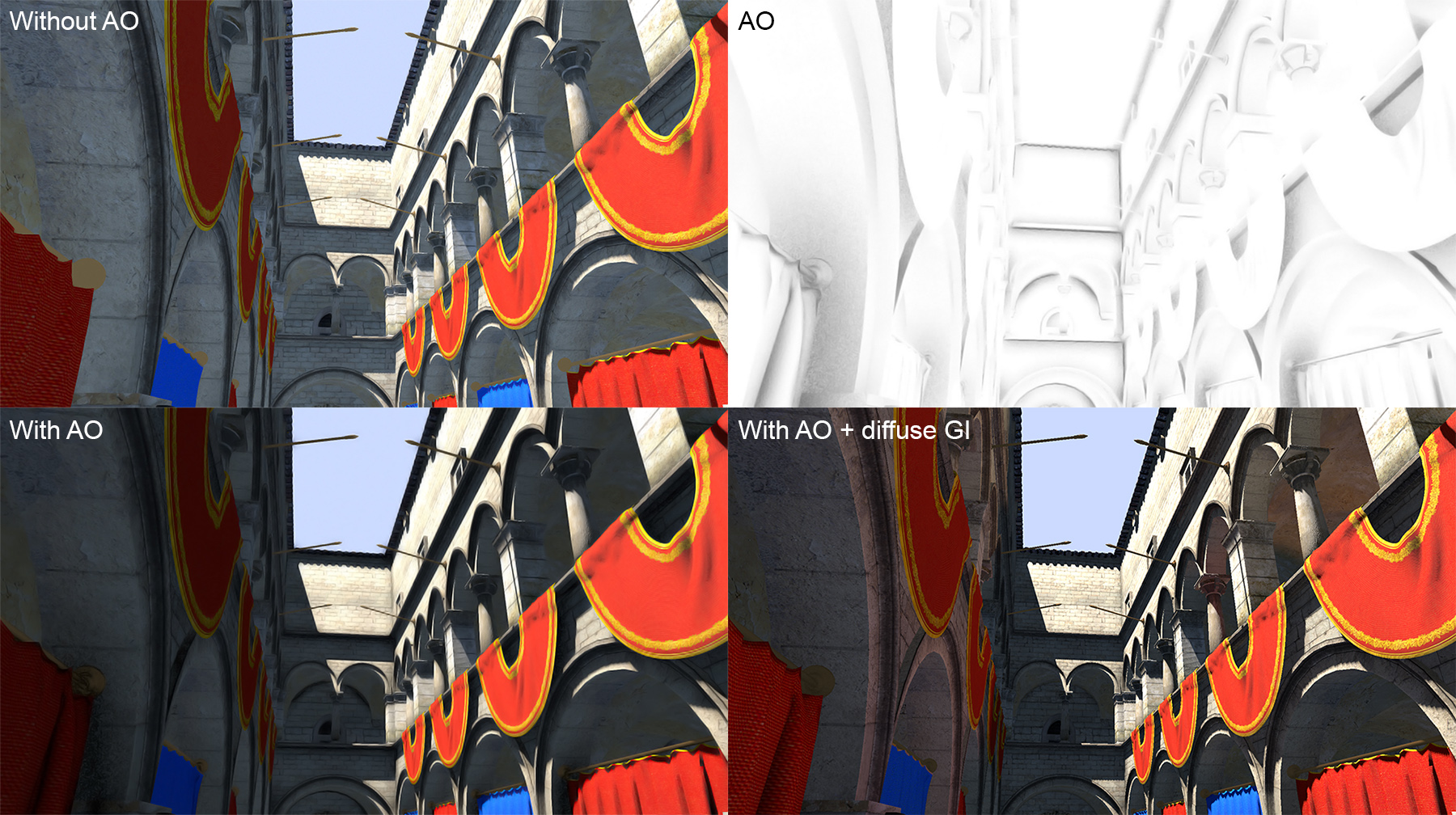

Texture-space shading is an orthogonal approach to the above, where instead of shading the sampled pixels of the image plane, shading samples are taken and computed on a texture image covering the geometry. The shaded textures are then used along with the conventional ones to draw the final image buffer, but with a far simpler (and faster) pixel shader, which only uses the computed lighting already stored in the texture-space rendering pass. In this method, the image buffer(s) correspond to the unwrapped textures that cover the objects (texture space) and their resolution can be significantly different than the output frame buffer. The shading density is also not constant with respect to the output frame buffer sampling rate, but can vary according to geometry feature importance, object distance, etc., providing many degrees of freedom to control shading quality versus speed. Texture-space shading also offers many opportunities for temporal re-use, as view-independent lighting information can be re-used across multiple frames. Despite its many welcome properties, texture shading also has generally higher memory requirements, as it needs to maintain separate shading textures per object instance (shading is not shared among instances of the same object) and also requires the preparation of a bijective texture map, which is not trivial and may introduce its own artifacts. However, in a more limited form, texture-space shading is very common in real-time rendering, to "bake" (pre-compute) or update on the fly, possibly amortized over frames, heavy illumination computations, such as diffuse global illumination (see light maps below).

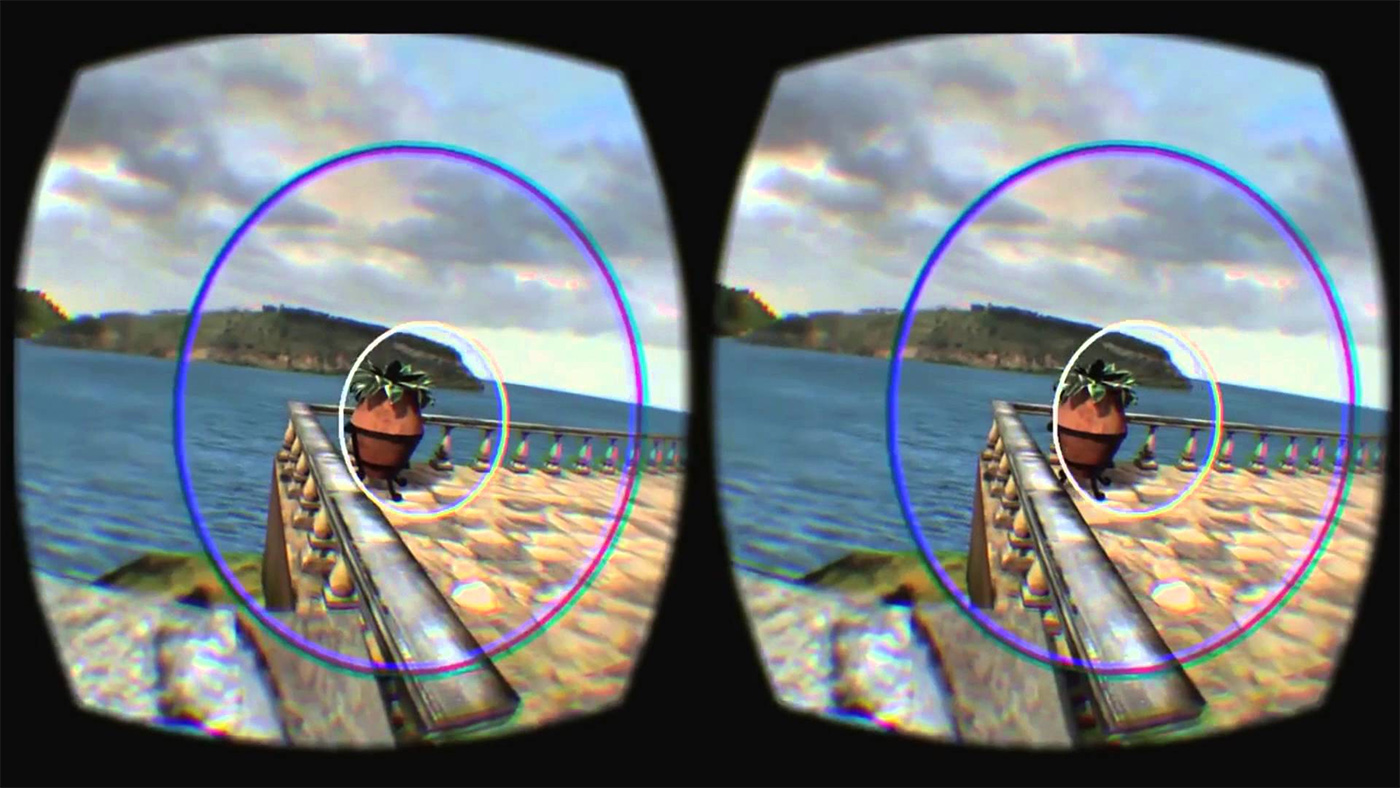

Decoupled shading can also refer to shading in any other parametric space and not necessarily a planar one. For instance, shading can be performed in object space, using volumetric representations, possibly in a hierarchical organization to allow for high spatial resolution, when needed. Furthermore, even simple forms of image-domain decoupled shading can adopt a non-uniform sampling rate, as is the case of foveated rendering, where sample density is higher near the gaze direction of the user and becomes lower in regions where the peripheral vision is more prominent.

https://www.geoweeknews.com/blogs/apple-bringing-3d-sensing-ar-vr-iphone.

Visibility and Shadows

Visibility between two points in space requires the existence of knowledge about the location of all other geometry that may cross the straight line connecting them, since we need to check for the intersection of that linear segment and the representation of the potential occluders. However, the rasterization pipeline operates locally on single primitive samples in isolation. Therefore, this global geometric information must come from outside the rendering pass that the visibility query is invoked from. Remember, it is very seldom that a visualization task involves only a single rendering pass. We more often than not perform one or more preparatory passes to produce temporary auxiliary buffers to be used later in the frame generation pipeline. This is exactly the idea behind one of the most popular single real-time methods used in almost every interactive rendering application: the shadow maps algorithm. Below we present the core idea and some extensions and variations, but also attempt to cover other visibility ideas associated with rasterization.

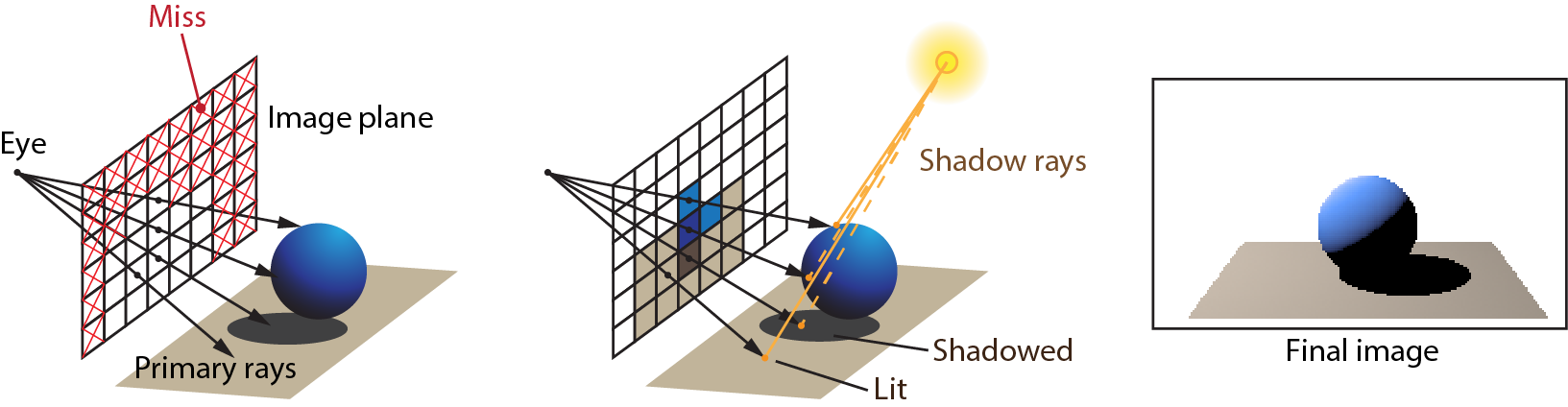

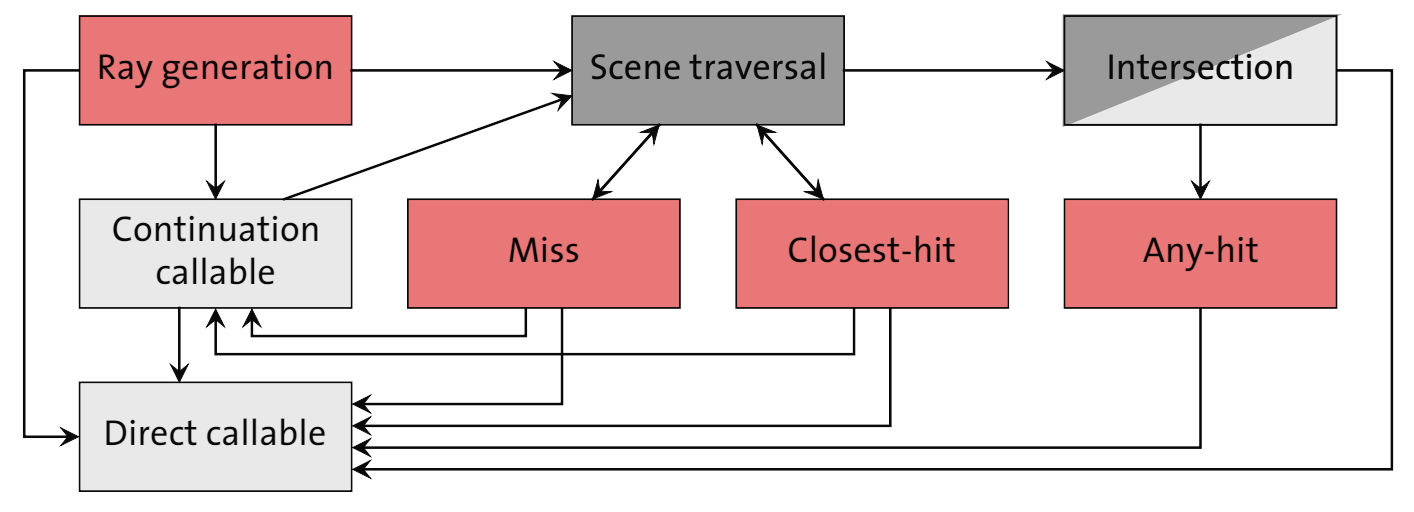

Shadow Maps

The shadow maps algorithm, which by design works for punctual lights with conical emission (a "spotlight") is based on a very simple idea: if something is lit, it is accessible by the light source and therefore it should be "visible" from the light source’s point of view. Since the lit primitive parts are visible to the light source, they must therefore be the closest to the light source. So if one were to render an image using as "eye" the location of the light source and as viewing direction the spotlight’s emission cone axis, the closest samples registered would be all samples on lit surfaces. We call this light source’s depth buffer, a shadow map (see next figure).

The algorithm operates in two discrete stages. Given a single light source, in the first stage, the rasterization pipeline is set up so as to render the scene from the light’s point of view, as detailed above. Since we are interested in forming just the shadow map, i.e. normalized depth of geometry from the light position, any color information typically produced by a pixel shader is irrelevant in the most basic form of the method, and is therefore completely ignored. No color buffer is enabled and no color computation is performed. In stage two, we switch to the camera’s point of you to render the shaded image as usually. Here we query the shadow map to determine whether a shaded point is in shadow or not. We do so by transforming its position to the same coordinate system as the stored shadow map information and then checking whether the new, transformed sample’s is farther from the recorded depth in the shadow map for the same and coordinate. If this is the case, the sample cannot be lit (in shadow), since some other surface is closer to the source and intercepts the light. Otherwise, the light source is visible (no shadow). The transformations required to express a camera-view image sample to the light source’s normalized space are all known: We have explicitly specified the world to camera and the world to light transformations (both systems are known) and we have set up the projections for both cases. The transformations are also by design invertible. The concatenated transformation matrices are supplied as uniform variables to the fragment shader and th process is quite fast.

The shadow maps algorithm is a prominent example of a technique where actual geometry is approximated by partial and sampled version of it. It is clearly also a case of decoupled "shading": we run a fragment shader to compute the shadow map which has a different and uneven sampling rate with respect to the camera-space pixel generation rate. In fact, the latter is actually a source of error in the process and one of the negative aspects of the method.

There are several positive aspects of using shadow maps for light source visibility testing and in fact, for several low- and mid-range hardware platfroms, shadow maps constitute the only viable real-time solution, despite the advent of ray tracing support at the hardware level of modern GPUs. Some of the advantages are as follows:

Full hardware support, even in low-end devices, since it only requires simple rasterization of primitives to work. Directly supports HiZ mechanism, where available.

Decoupled and scalable rendering quality. Shadow maps resolution is independent from the the main view resolution and can be tuned for trading performance and quality.

No extra geometric data are produced and maintained in the GPU memory (e.g. acceleration data structures in the case of ray tracing). The shadow map fills the role of the scene’s geometric proxy for the task of visibility testing.

Directly compatible with the primary view in terms of representation capabilities. They both use rasterization and fragment-based alpha culling, supporting the same primitives and effects.

Simple and intuitive 2-pass algorithm with linear dependence on scene complexity.

Shadow maps are easy to combine with and integrate in other effects, such as volumetric lighting (e.g. haze, godrays).

On the other hand, there are several limitations and problems that come with a) the specific setup for the light projection and b) the fact that shadow maps are a discretized representation of the virtual world, causing sampling-related artifacts and precision errors. More specifically:

Simple shadow maps require projector-like light sources. A single-pass shadow map generation stage with the most basic setup, can only capture shadows from projector-like (spotlight) or directional light sources, since it requires the configuration of a regular projection (perspective or orthographic, respectively) to record the closest to the light source geometry samples. Omni-directional light sources must render the depth information in more than one shadow map buffers, such as cubemap shadow maps and dual paraboloid shadow maps. Using additional projections fortunately does not imply the emission of the geometry multiple times in modern hardware, since replicating the geometry and "wiring" it via different projections to multiple frame buffers can be done with geometry instancing and/or layered rendering in a geometry shader. Still, even this, breaks the simplicity of the algorithm and incurs some additional cost.

Only work for punctual or directional light sources. Shadow maps with a perspective projection require a single center of projection. It is therefore impossible to query visibility of samples distributed over an area light source. The only options for approximating area lights are: a) temporally change the center of projection and respective transformation and average (blend) the results in camera image space. This incremental approach can work for stable views only. b) Fake the area light by jittering the camera-space fragment position within the fragment shader and combine visibility samples and c) jitter the shadow-map (image) space samples and average the visibility results to mikic soft shadows. The latter is also used for shadow mapping antialiasing (see below).

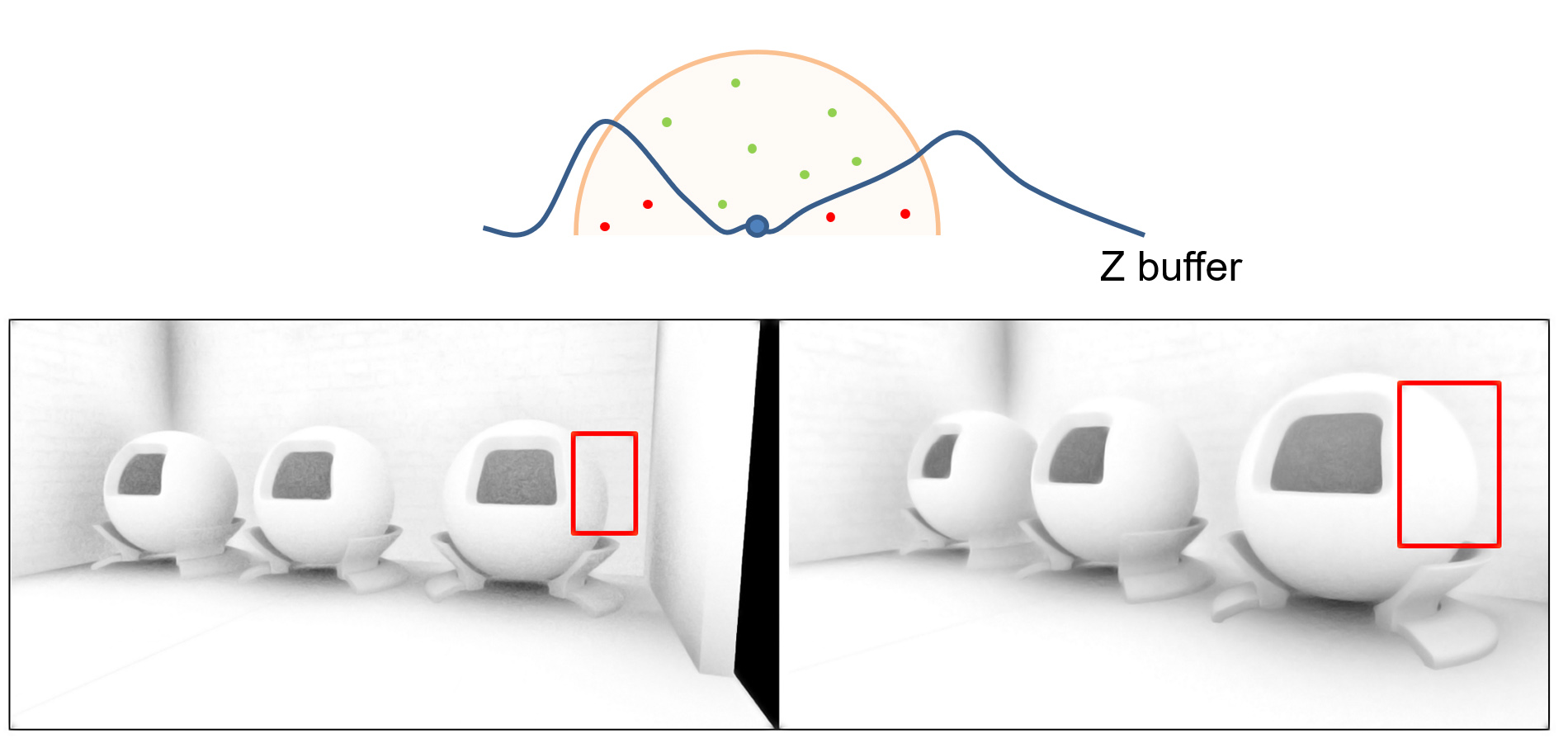

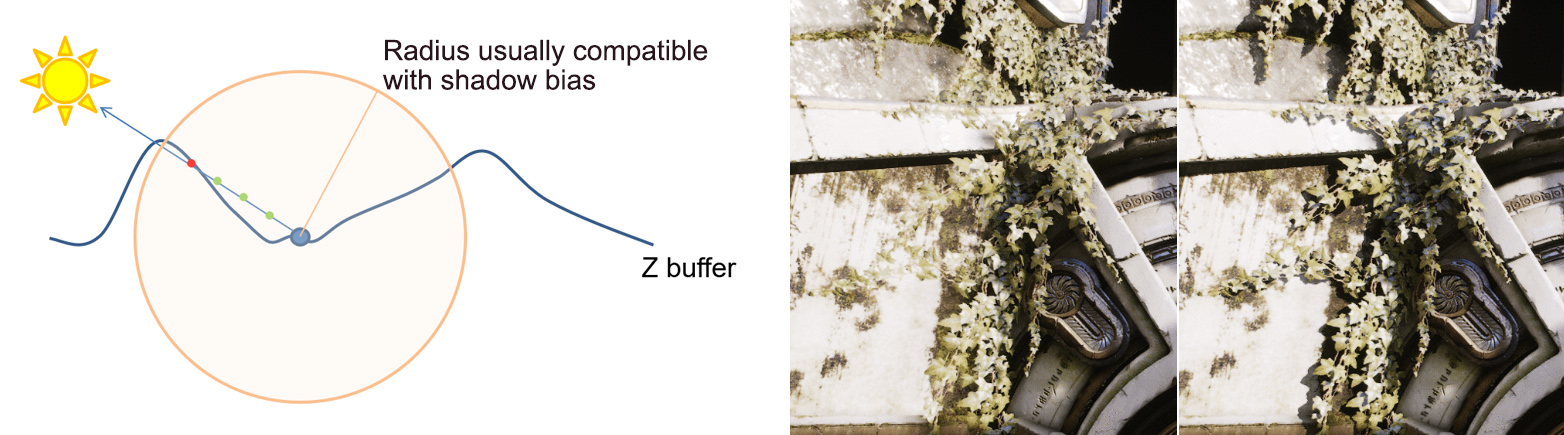

Cause under-sampling and pixelization artifacts. Camera fragments are produced with a specific screen-space sampling rate and are then unprojected, affinely transformed and re-projected to the shadow map space. This means that the resulting sampling positions are generally completely incompatible with the rasterization rate with which the shadow map has been produced. Severe aliasing can be produced due to the density of the projected camera fragments being either higher than the shadow map pixels, resulting in pixelization artifacts, or lower, causing under-sampling errors and flickering. The problem is demonstrated in the following figure (areas highlighted with green). Both problems are partially alleviated by sampling the shadow map using percentage closer filtering (PCF) or some similar visibility estimator. PCF draws multiple depth samples, instead of one, in the vicinity of the projected fragment onto the shadow map and averages the visibility decisions for each shadow map depth. Simple texture filtering on the shadow map, which is a depth image, does not work.