Historical Background

(Source: A. Benardou, A. M. Droumpouki, G. Papaioannou, First-person Interactive Experience of a Concentration Camp: The Case of Block 15, Difficult Heritage and Immersive Experiences, A. Benardou, A. M. Droumpouki - Eds., ISBN 9781032060866, Routledge, pp. 145 - 160, 2022. )

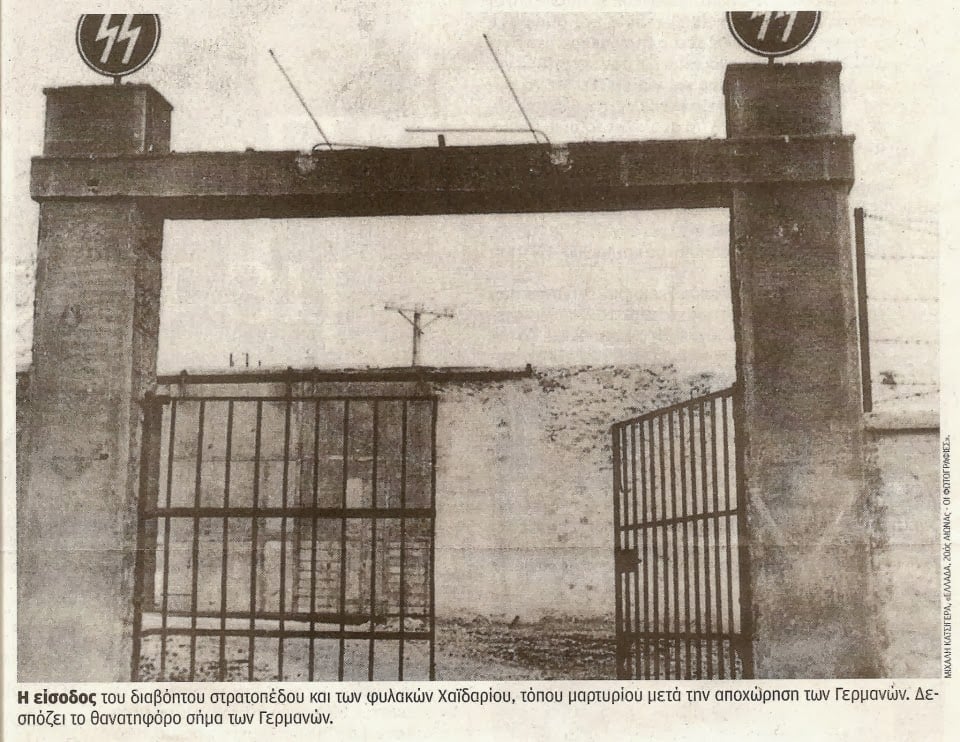

The German occupation of Greece from April 1941 to October 1944 claimed more victims in relation to the total population than in any other non-Slavic country. Despite growing interest of both scholars and the public in highlighting sites of memory, there has been no effort to understand the spatiality of the wartime period in Greece, due, in large part, to difficulties of access, or absence of knowledge, around sites at all scales, from killing sites to concentration camps. There is no comprehensive study of the German concentration camps in Greece, even statistical data or relevant archival material hardly exist. Almost only memoir literature as well as oral and public history are available for research. Of the presumably 36 (and not further specified) concentration camps set up by the Germans - with over 100,000 prisoners and 48,000 executed - Haidari in Attika and Pavlos Melas in Thessaloniki are among the worst.

Concentration camps are the fundamental instrument of control and punishment for the occupation policy across Europe. The enormous social and cultural impact of the camp experience has meant that smaller places of internment, such as forced labour camps, transit camps, prisons and jail houses, which played no smaller role in the vast system of repression within which they were integrated, have, nevertheless, been largely overlooked. Greece is largely obsessed with the preservation of the past. However, this obsession is focused, almost without exception, on Ancient Greece and Classical antiquity, with very little research undertaken on the concentration camps of Occupation Era Greece. Indeed, the history and transformation of concentration camps and prisons during the Occupation Era, both Italian and German, remains an intriguing but rarely researched subject. The former concentration camps of Haidari in Athens, Pavlos Melas in Thessaloniki and the Italian and German concentration camp in Larissa exemplify the problematic materiality of memory in heritage. In all three cases, site deterioration is due to neglect. Τhese camps have not been declared ‘heritage sites’ as other similar sites have been elsewhere in Europe. There has been no “memory boom” in Greece of the type that has characterised renewed interest in the materiality of the Second World War in Europe. Indeed, the Second World War remains inaccessible to those attempting to connect with the period through surviving ruins, while memorial sites of the 1941-44 period exist, largely, in a state of decay; crowning the silence which characterizes the memory culture of the 1940s in Greece more widely.

The concentration camp of Haidari is 9 kilometers west of the capital Athens. The Haidari camp was built in 1937 during the Metaxas dictatorship and served as a training center for the Greek army. However, the construction was not completed. The site is located at the foothills of Pikilio Hill north of the Athens-Corinth road. In the beginning, the camp functioned as a branch of Averof Prison on Alexandras Street. After the outbreak of the Greco-Italian War, it was "inaugurated" on September 3, 1943 as a concentration camp with the transport of 590 prisoners from the Italian Larissa camp, which was to be closed. Among the 590 prisoners counted by the camp doctor Antonis Flountzis there were 243 communists from Akronafplia prison, 20 prisoners from the island Anafi as well as another 327 prisoners of the Italians. Among these first prisoners was Flountzis himself, which means that his information can be assessed as relatively credible. The Haidari camp was primarily a transit camp for the prisoners on their transport to the concentration camps in Germany or Poland, and the same conditions and rules prevailed as are known from all other types of horror during the Nazi regime.

On September 10, 1943, after the Italian surrender, the Sicherheitsdienst (security service) took over the former barracks to “concentrate” suspects who had been arrested in connection with resistance actions or raids. Haidari also became a transit station for thousands of Jews who were deported to Auschwitz. The facilities of Haidari extended over approximately 50 hectares. In the whole camp there were about twenty block buildings or barracks, as well as larger and smaller barracks, each of which served different purposes. The block buildings were divided into two parts, each with its own entrance. There were two prisoners categories: the first category was placed in the so-called “free camp”, the next in “light solitary confinement” in the cellars of Block 4, while the last category in Block 15 was subjected to complete isolation. The Germans had set up sewing and wood workshops as well as a shoe and equipment production facility in the camp, in which prisoners with the appropriate skills were employed. There they repaired furnishings that had been confiscated in Greek private houses and made shoes and civilian clothes from materials that had been stolen from various cloth and leather warehouses in Athens. The articles produced were intended for the various SS services or were sent directly to Germany. The inmates of the Haidari concentration camp were also sent to other “work” outside the camp, such as following the bombing of Piraeus. There were also accommodations for guards, administration barracks, a kitchen and storage sheds. There were hardly any washing facilities, so the hygienic conditions in the camp were unsustainable. It is known from testimony that many of the prisoners went blind due to the poor living conditions and the lack of vitamins. For example, the sewage pits were deliberately rarely emptied, which meant that the prisoners had to relieve themselves in the corridors and stairs of the block. The toilets in Block 15 were full of feces and the sick collapsed in the midst of the excrement.

An estimated 20-25,000 people were imprisoned: men and women, prisoners of war, partisans, members and officials of the Communist Party of Greece, Jews, hostages arrested in purges, political leaders such as the leader of the Liberal Party and later Prime Minister Themistoklis Sofoulis, or the ministers and former premiers Stylianos Gonatas and Georgios Kafantaris. Some well-known personalities from the intellectual and cultural life of Greece were also imprisoned in Block 15, including the actress Rena Dor, the Professor Emmanuel Kriaras and his wife, the composer Nikos Skalkotas and, for three months, the actor Giorgos Oikonomidis. Professor Emmanuel Kriaras, then director of the Medieval Archives of the Academy of Athens, was detained in Block 15 for three days. His brief testimony describes life in prison and isolation.

Since the beginning of 1944 Chaidari was an internment place for various groups of people, so for members of the leftist resistance and the conservative partisan organization, for members of espionage networks and British services, for trade unionists, students, workers, high officials, in individual cases even for members of the collaborating Greek Security battalions and members of German services who had been charged with contacts with the Allies or criminal offenses. In November 1944, the New York Times reported that Chaidari was one of the largest Nazi camps in occupied Europe, which shows that the camp had achieved dubious fame well beyond the Greek border.

The fate of the prisoners was extremely tragic. A life-threatening workload, constant malnutrition, a lack of medical care, fatal living conditions, lack of water, constant harassment and arbitrary murders characterized their everyday lives. Unfortunately there are no death registers left, which makes a general balance of the victims of the Haidari concentration camp impossible.